Wild, Remote, Endless

Everytime Anthony visits Washington, he gives me a call and we plan something big. Two months ago, we sent the Isolation Traverse in an amazing 17 hour North Cascade skimo dream. Each time he leaves, it gets a little harder for him to say goodbye to our lovely state. This time, he was visiting with his best friend Danny. He mentioned he had heard about this mysterious “Pay-satan” Wilderness area. That was all the encouragement I needed.

Two summers ago, Kylie and I were driving around the west and made a last minute plan to visit Salt Lake City and climb there. Anthony was the only person I knew there so we gave him a call. He was just getting off skiing Denali, but immediately promised we could stay with his friend Danny. We showed up at his door and Danny kindly obliged and gave us recommendations to a successful week in Salt Lake, climbing some awesome stuff like Mt. Olympus and Mt. Superior. It felt like the quintessential SLC experience, to scramble thousand foot ridges and slabs hanging out over town. Now it was my turn to give him the quintessential experience of our state’s biggest wilderness area, the Pasayten.

Four summers ago, my dad and I spent four days in the Eastern Pasayten, losing ourselves amongst endless fields of wildflowers, stretching views, and broad ridges. Since then, I had not returned, deterred by the long drive and lengthy approaches, but it had left a strong feeling in my heart, something few places can do. I knew I would be back when the time was right.

After a peaceful night in Mazama, we drove up to Hart’s Pass. This was my first time driving to Hart’s Pass, which is considered by many to be the highest drivable road in Washington.

The biggest delay was from a family of mountain goats chilling in the road.

Anthony’s friend Wade, who he also met on his 2017 west coast bike tour, was also joining us for the day.

It was unseasonably cold at the upper Slate Pass trailhead, so we quickly started on our little 20 foot uphill to Slate Pass. Then it was all downhill – at least for a few hours.

We starting jogging down through rocky larch gardens and then fields bursting with avalanche lilies.

By the time we crossed the Middle Fork Pasayten River, Wade was minutes behind. It was clear he would not be able to keep up. We talked about it and agreed that he would proceed towards Lago by himself and we would hit Lago from the backside, possibly catching him on the climb back to Slate Pass.

The Middle Fork Pasayten Trail to the Fred’s Lake turnoff is in pretty good shape, at least for Pasayten standards. There are a handful of blowdowns, but the downhill trend makes it easy to hurdle them in stride. Even in the forest, the flowers are impressive and continuous.

In front of me, Anthony suddenly stopped in confusion. “What are these birds?!” It was a mommy ptarmigan and her babies just in the middle of the trail!

Past the Fred’s Lake turnoff, we crossed a huge burn zone on the slopes of Point Defiance. The blowdowns were in the hundreds here and we had to tediously jump from log to log, gouging ourselves in the snags occasionally. Blood has been shed.

We branched off on the connector trail to the Tatoosh Buttes and things marginally improved before getting bad again in the burn near Lease Creek. 15 miles, a thousand or so blowdowns, nearly all downhill. No way we were going back the way we came. We were committed. Sometimes that is the best way to adventure – leave yourself with no real alternative but to plow ahead. It certainly felt appropriate for the remote Pasayten.

We continued over blowdowns and headed straight uphill towards the Tatoosh Buttes. Luckily, we stumbled across the trail and it became quite good once it got above the trees in a few hundred feet. Suddenly, we were gazing out across the Middle Fork Pasayten River Valley – the largest valley I have ever seen in the Cascades. The width of this valley felt so foreign, like a valley in the Brooks Range of Alaska or the Canadian Rockies. The North Cascades are like, in Anthony’s words, “a dozen Wasatches packed into one”.

After a monotonous 15 mile downhill to start the day, we felt the stoke returning with every step higher. The mountains were opening up with such scale. In the Pasayten, yards become miles and hours become days. You could disappear here and never be found. That’s how wilderness should be.

We could see the steep, rugged north faces of Osceola, Carru, and Lago across the valley. It got Anthony and Danny jazzed to see our objective: the alpine ridge from Tatoosh Buttes to Lago.

The Tatoosh Buttes were a wonderland of open meadows, endless views, chirping birds, and trickling springs. Pure Pasayten magic. It was trail running heaven.

We left the faint trail and began traversing the open slopes of Tamarack Ridge. The confluence of wildflower meadows with bright green larch groves was quintessential Eastern Cascades. We even saw a male ptarmigan, noted by its red eyelid.

As we gained the shoulder of Ptarmigan Peak, the meadows were quickly replaced by alpine tundra reminiscent of the Brooks Range or the Scottish Highlands. Here, life was continually challenged by cold temperatures, high winds, and thin soil.

The summit offered clean 360 degree views off to Canada, the endless rolling hills of the Eastern Pasayten, and the rugged, snowy heart of the North Cascades.

Summit breaks are always short with “Impatient Anthony” so we were quickly headed down the easy south slopes of Ptarmigan. Lago still looked so far away, but the traverse looked absolutely awesome.

On the south slopes of Ptarmigan, there is this perfect little tarn at 7800 ft. From here, all one can see is the infinite sky and infinite-seeming North Cascades in a veil of tempered glass. Completely alone, in the center of it all.

One thing I love about the Cascades is not just how each region appears unique, but how each region fills me with a unique feeling. The Cascade River Road and Pickets inspire awe and fear. The Stuart Range seduces. The Glacier Peak Wilderness is love. The Pasayten is… loneliness. Sometimes it is in these lonely places where we feel most connected to the land and world around us.

Dot Mountain was an easy walkup. The ridge then became a little more knife edged towards Pt. 8165.

Pt 8165 had some class 3 scrambling. The rock was surprisingly solid. We were in such a grove at this point that movement was fast and easy. Instead of going around, we continued directly on the ridge also over Pt 8207, which had the steepest scrambling of the trip.

The feeling of moving across such huge, remote terrain was truly indescribable. It feels invigorating, intoxicating, empowering. It is the clearest metaphor for the magical power that comes at the confluence of dreams, desire, and drive.

The final ridge of Lago turned to dark, lichened covered rock. Behind us were shades of orange, gray, white, and green – colors of the Pasayten.

When I plan a trip like this, I don’t start with an objective. Instead, I work backwards; I think about crafting an experience, an experience that captures the feelings of the region. When I envisioned this trip, I saw broad remote valleys, tundra ridges, and endless wildflower meadows. I felt commitment, loneliness, and wonder. To me, this is the experience of the Pasayten Wilderness. If you have a clear vision of the experience you seek in the mountains, the rest will fall in place. In the North Cascades, the canvas is infinite. See where your brush strokes fall.

Anthony called Wade from the summit. Unfortunately Wade had been attacked by a hawk and turned around there! At least he was not too badly hurt…

We trended skier’s right from the summit towards the Lago-Osceola drainage. The talus was usually 6-12 inches in size and very movable. It made for a slow, painful descent as none of us wanted to get injured so far out. Danny’s shoe was falling apart, which worsened things.

Further down, we got funneled into a steep waterfall drainage. Amongst the roaring water, Anthony and I got separated from Danny. When we finally found Danny above some cliffs on the other side of the creek, he and Anthony started yelling at each other in frustration, but the words were lost in the sound of water. I guess spending too much time together can do this to people…

After a soul crushing 3000 ft descent, we finally found the trail at the bottom of the valley. The descent had completely demolished Danny’s shoe.

We slowly grinded uphill towards Rolo Pass. The beautiful views down Eureka Creek and abundant wildflowers kept our minds entertained, but there was no hiding the fact we were all getting pretty fatigued.

We passed Freds Lake and its stunning green waters.

We bombed the descent back down to the Middle Fork of the Pasayten. Now it was “only” a gradual 9 mile climb back to the car. What a way to end a huge adventure run!

Anthony took off ahead of us and I slowly pulled away from Danny. I heard some shrieking and then suddely, Wham! Something slammed me in the head. It was a hawk! I screamed out louder than I probably ever have. Then I catiously watched the hawk, anticipating another attack before scooting by. It did not draw blood, luckily, but it was terrifying.

A mile later, I decided to wait for Danny to make sure he was okay. Turns out he was the only one in our group would did not get attacked (we later learned Anthony got bombed too). Regardless, it was nice to have company as we jogged/hiked the final few miles to the pass.

All in all, this was the biggest day I’ve ever had in the mountains, more rugged than the Timberline Trail and more distance than Glacier Peak. I’ve made huge strides this year not by training more or running faster, but simply by being wiser about how I pace myself, fuel, and hydrate. Still, it was a little surprising to still be cruising at 15 minute miles uphill at the finish.

As we emerged into the alpine one last time, moody clouds were swirling once again and evening light was fading. A cold wind reminded us not to dwaddle, although the infinite fields of avalanche lilies begged us to stay.

As we topped Slate Pass, Anthony gave us a holler from the car. Smiles, mountains, and beauty all around.

This is the Hart of the Pasayten Wilderness. Wild. Remote. Endless.

Notes:

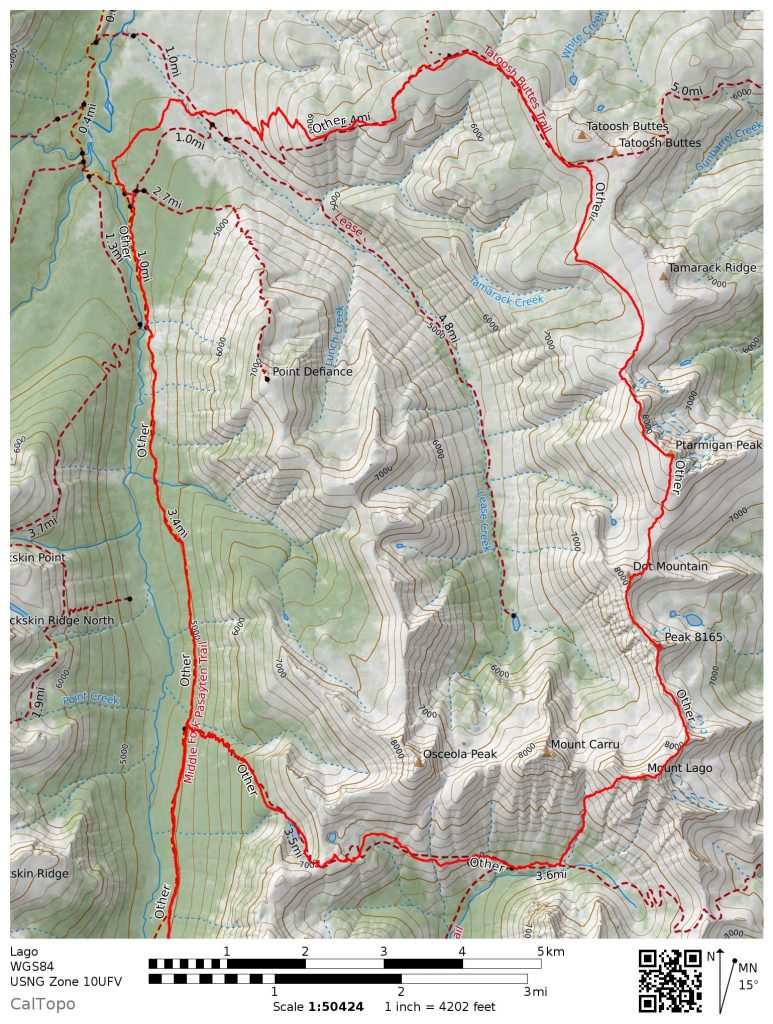

- Our route was about 42 miles and 11,000 ft gain. 9 of those miles were completely off trail. Many of the other miles were on abandoned trail. It took us 14 hours.

- The Middle Fork Pasayten past Freds Lake turnoff deteriorated rapidly with blowdowns. This slowed us down greatly.

- Many trails in the Pasayten are not where GPS maps are, so you cannot rely on GPS for finding abandoned trails.

- The traverse from Tamarack Ridge to Lago had no running water with the exception of the little tarn on the south shoulder of Ptarmigan Peak. I believe this would last into late season. Otherwise, there is plenty of water.

- The ridge traverse goes at class 3. You can easily go around the class 4 sections we did, but the rock is surprisingly good and fun.

- Our descent down Lago sucked. Perhaps try going skier’s left from the summit? I think that is the standard route.

- We were barely able to drive to Slate Pass (a week ago there was still a snow patch on the road) so this is about the earliest you can get up there.

- There’s so much potential for adventure running in the Pasayten. It’s wild out there!

Update 7/16/20: Apparently some trail crews have cleared most of the blow downs we encountered on the Middle Fork Pasayten and Tatoosh Buttes trail. Thanks!

I was looking forward to this report and it did not disappoint! I have this one high on my list and it remains there after reading this. Awesome effort!

Thanks Stuke! It’s definitely a worthwhile route!

Awesome trip report and pictures! A friend and I did a similar loop in 2018 but counterclockwise, and must have spent at least half an hour finding our way from Lease Creek over to the Buckskin Ridge Trail because of all the blowdowns and false trails. There was a WTA trail crew on the north section of the Buckskin Ridge Trail that said there were 400 blowdowns across it.

We took a similar route to your decent up Lago, but gained and stayed on the arm you started to come down on vs going further into the drainage.

Very cool! It’s tough for any trail crew to maintain an area like that with so much deadfall potential.

Great adventure and write up!

I just did Buckskin Ridge back via Robinson Creek/Middle Fork. There were a few blowdowns at the North end of Buckskin, but not too bad. RC/MF was totally clear and made for smooth and easy running. It’s probably time to make a donation to the WTA after seeing the piles and piles of cleared trees that I was fortunate to have avoided.

That’s great to hear! It can be hard to know which organization actually did the trail work, since Okanogan Wenatchee, WTA, PCTA, and PNTA (mostly the Boundary Trail) all do a ton of work in the Pasayten.