Table of Contents

Putting it all Together

Disclaimer: I have no formal education in meteorology. I take no responsibility for you getting skunked, pissed on, or washed off your objective. This is the Pacific Northwet, after all.

In my previous three weather blog posts, I have discussed basic weather concepts, listed weather resources, and talked about particular local weather nuances. For my final post, I will bring all these ideas together by discussing my process for trip planning with a focus on mountain weather.

I will demonstrate my planning process with weather for a summer high route, winter ski tour, and spring ski mountaineering objective. Each of these examples should give you and idea which resources I use and what factors are most important.

TLDR: Follow weather daily to spot weather windows. Monitor a variety of sources and match your objective with your quality of conditions and risk / failure tolerance.

Summer High Route

In the summer, we are generally blessed with relatively mild weather. It is not usually too hard to find a solid one day weather window. If restricted to weekends or looking for a multi day window, it can be more challenging. Here are a few common questions I ask when planning a summer high route and how I will answer those questions.

Is there a weather window approaching?

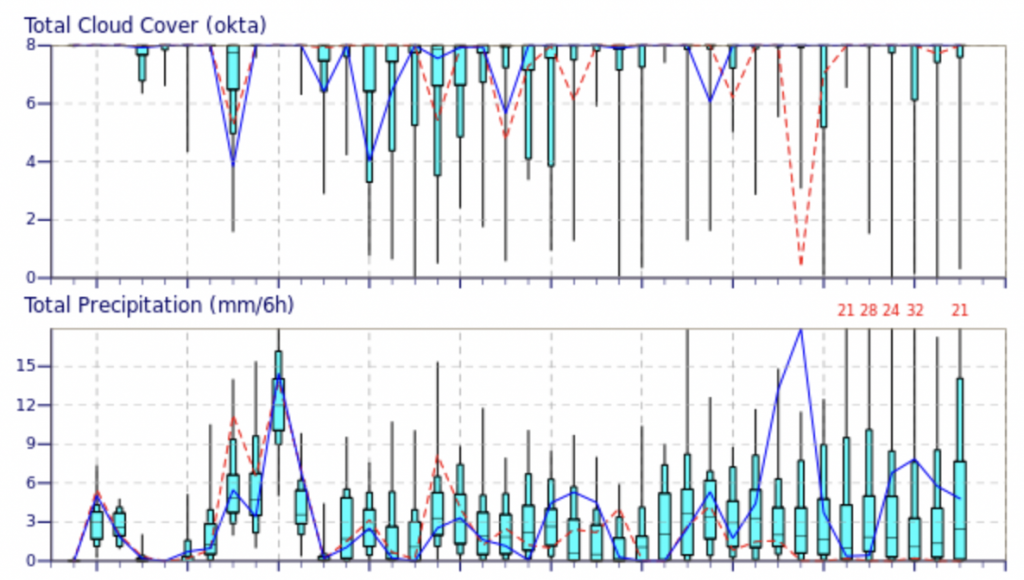

For getting an idea of the 5-10 day picture, I check out the ECMWF ensemble members. Given the length of my proposed trip, I look for days that show a very low probability of rain and cloud cover, i.e. the 90th percentile in the precipitation graph is no precipitation, and the 75th percentile for cloud cover is little or no clouds. This suggests that high pressure is coming. It is obviously no guarantee, but this can inform me if I should start making preparations like finding partners, securing days off from work, etc. As we get closer, I monitor specific point forecasts with windy.com and NWS.

How hot will it be?

Match the objective with the temperatures. On a cold summer day, choose a south facing rock climb not something shaded like the NW Face of Liberty Bell. Trail runs are often nicer on a cool, partly cloudy day, when the high peaks are still socked in. Heat can get to the best of us, so I want to make sure temperatures are acceptable for the objective. Smoke is also another consideration.

Will I be stuck in a cloud?

The trickiest part of the summer forecast is marine layers and clouds on the west side of the Cascade Crest. The windy.com meteogram can be helpful for estimating cloud layers. The NWS forecast discussion often discusses the strength of a marine layer and when it might burn off. A lot of predicting this just comes from experience, learning which spots hang on to clouds, and how to read the forecast. Ultimately, this is a bit of a crapshoot.

How much snow is left?

This is most easily answered by recent trip reports and Sentinel satellite imagery. Usually it is not that hard to find a cloud free image in the last week or two during the summer. This can inform your decision about timing routes and if certain snow travel gear is needed.

What is your failure tolerance?

Ultimately, you cannot change the weather but you can change your objective. Sometimes the forecast looks borderline, and it is challenging to guess if it will work out. In most cases, you can improve your chances of success by swapping that alpine climb for a trail run or going to climb dry rock in the Stuart Range instead of Darrington. This is a personal choice. How much do you want a specific objective? Are you willing to be realistic with your chances of success and accept failure if the weather does not cooperate?

Personally, I have found the most success by being adaptable and waiting for the best conditions on the objectives that are most important to me. When trying to pull something off that is close to my physical or technical limit, I want to minimize things that could go wrong. If the weather is questionable, then that is just another potential downfall, along with my fitness, technical abilities, gear, route finding, etc. There is always something to do in the mountains, and sometimes you just have to take what they give you. Patience pays off.

Winter Ski Tour

For a winter ski tour, I use many of the same resources as summer trips: Windy.com, NWS, etc. However, rapidly changing snow conditions here demand much greater detail. In this section, I will cover additional questions that I ask when making a plan for a typical winter ski tour, where I am hunting for good snow.

What is the Avalanche Forecast?

NWAC is the place to start for the avalanche forecast. The avalanche forecast and avalanche problem informs which terrain is even reasonable in the given conditions. Additionally, reading about the snowpack status can give you clues to where you will find better skiing, or if skiing is even worth it. You should be following along with the snowpack throughout the season to get an understanding of where weak layers are and how it varies by region.

What are snow conditions in different regions?

Winter ski touring here is unfortunately rather limited to the key access points like ski areas and mountain passes. Recent observations can be helpful. There is great telemetry on NWAC’s site showing precipitation, winds, and temperatures for nearly all the major spots. All these parameters affect the snow quality and avalanche hazard. I encourage you to verify the avalanche and weather forecast by looking at the data: did it really warm up like expected? Were winds stronger than forecasted? I frequently audible the morning of a tour if telemetry turns out differently than the forecast when I went to bed the night before.

When it comes to translating telemetry to ski quality, it takes a lot of experience. How much fresh is required on top of a rain crust at X density to not feel the crust in Y degree terrain? Pay attention to layering in the snowpack, temperature gradients, and how wind plays with terrain. I talk a lot about these details in my previous blog post. Ultimately, you are still going to get it wrong a lot of the time. I am wrong much of the time. But learning is part of the process.

When was the last precipitation recorded?

When it snows overnight, you do not have to go far to find fresh tracks. Additionally, after large dumps, long approaches might simply not be viable in deep powder. But if it has not snowed for a few days, you might want to push further to find fresh tracks, and oftentimes there will be better stability too (but this is not always the case). The quality of the top layer of snow is also important in determining ski quality. Did it fall with rising temperatures or lowering temperatures? Was it very wind effected? Might the snow be more protected in the trees or on certain aspects? Do we need to go as high as possible to get above the rain line?

Which tour should we do?

Once I have an understanding of the avalanche forecast in that region, decided on a region, and thought about the type of terrain I want to travel through, I think about specific tours. The tour plan should align with the avalanche forecast and the team’s goals and abilities. If there is more uncertainty in the forecast, I will usually plan more conservatively to allow in field observations and easing into more consequential terrain with the option of staying in safer terrain. Typically, in all but the most surefire weather and avalanche forecasts, I prefer flexible tour plans that given many options, rather than putting all my eggs in one basket and attempting an objective that has poor backup options. But it all depends on what you are trying to get out of the day.

Will driving and parking be reasonable?

Unfortunately, part of winter recreating here is dealing with crowds and traffic. US2 is notoriously bad, but I90 closes more frequently. Consider the logistics of your trip plan. Is the slightly better powder at Stevens really worth an extra hour of traffic? It is up to you. But be sure to check WSDOT highway cams and reports before you head out.

Once in the field, what are observations telling us?

Planning does not stop once you start skinning. Feel the snowpack as you skin upwards. Is it aligning with your expectations? Is there wind effect where expected? Finding good, safe slopes to ski is a continuous game and you must be paying attention to the clues the mountains are giving you. I have had many days where the first run is poor, but we gather information and find great powder by the end of the day.

Spring Ski Mountaineering Objective

Evaluating the weather for a spring ski mountaineering objective follows many of the same principles but also demands more attention to snow coverage and solar effects. It often requires extrapolating data because there are not precise snow measurements and forecasts for more remote areas. Usually, I have more of an adventure or objective mindset with spring touring, rather than focusing mostly on the quality of turns. Here are a few questions I will usually ask throughout the spring.

Where is snow line / how deep is the snowpack?

As things melt out in the spring, it is important to follow the snow coverage in different areas. One useful tool is the USFS snow depth map which predicts snow depth over various regions. The most objective measurement is snotel sites, but obviously their coverage is limited. You can also look at SentinelHub for recent satellite imagery. Additionally, trip reports from various sites can be helpful. Timing trips based on the meltout is very key. Go too early, and you might have to skin on a road a long ways or deal with a still transitioning snowpack. Go too late, and you might have to bushwhack and take your skis on and off frequently. Even worse, a couloir might be melted out and require a cruxy down climb on rock with running water. It is helpful to keep tabs on the relative snowpack depth in different regions, looks at trip reports from years prior, and stay connected with others for beta.

Can I drive to the access point?

This is one of the most challenging parts of spring planning in the Cascades. Roads can hold snow even when slopes above them are melted out. Even if the snow is gone, who knows if the road washed out or has fresh deadfall. To answer this question, I leverage all my resources – friends, locals I know, certain Facebook groups (PNW Peak Baggers like to do weird things and drive up obscure roads, Washington Off-Roaders get after it), people’s Stravas, everything. I really wish there was a better solution to this problem. Nothing sucks more than driving out and getting blocked many miles from your access point. If you have the means, bring a car with good clearance, a tow strap, winch, shovel, chainsaw, and pack some bikes in case.

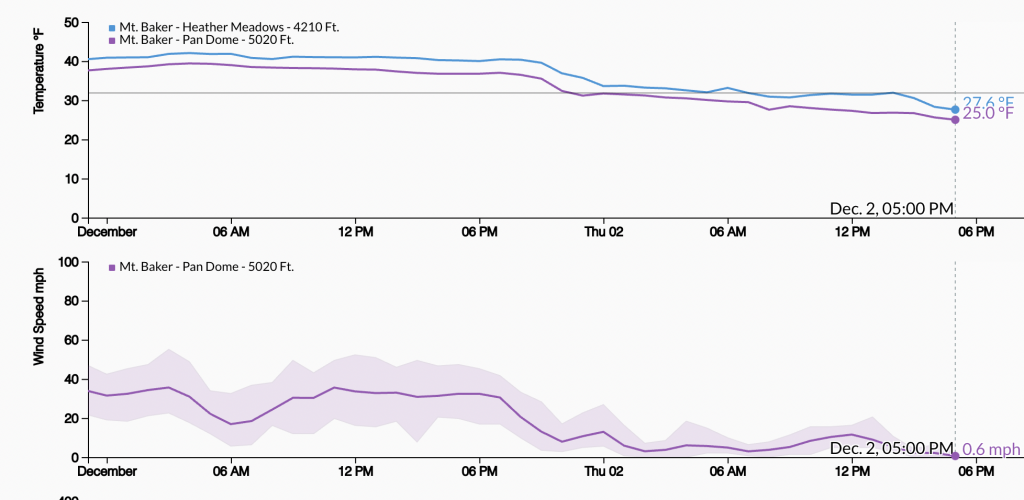

Will the snow refreeze overnight?

I go into more detail about this topic in my previous post. Getting a solid refreeze is the key to a safe, successful spring tour. Refreezes depend more on cloud cover (or the lack thereof) than temperature or freezing levels. Even in moderately warm conditions, I have found the surface of the snow will usually at least get a weak refreeze above treeline if the sky is clear overnight. If there are clouds or trees, the snow is less likely to refreeze. Colder overnight temperatures also help. The depth of the refreeze and the daily temperature and sun will together determine corn ‘o clock the following day.

How will the sun affect the tour?

This is a complicated question, because it involves guessing the strength of the refreeze, the strength of the sun and warmth of the day, and analyzing the terrain you will be traveling in. Caltopo has sun shading and allows you to see which terrain is in sunlight at any given point in the day. However, it takes experience to project when a slope will corn up and when it will destabilize. When in doubt, it usually pays to be early and wait if necessary. Eastern aspects corn up first, then south, then west. At some point in the day, northern aspects might also. If the tour involves multiple aspects, like most spring tours do, I will usually prioritize the most consequential terrain or the best descent. Few tours allow you to ski perfect corn on every descent and have firm bootpacks on every climb, but you can at least ensure that one is good and you can safely achieve your goal. Remember that safer travel (although usually not as good skiing) can also be found on slopes once they have gone back into the shade, so sometimes it pays to be late.

Adventure Awaits

As I have hinted at many times, the most important part of planning with mountain weather is being a student of the mountains. Even the most seasoned traveler is still surprised from time to time. I am often wrong in my predictions, and while it sucks to see someone’s Strava and realize you totally made the wrong decision, take it as a feedback and ask yourself what you learned today. Next time you will be smarter. There always is a next time.

This post concludes my “Weather in the Cascades” series. Understanding weather and choosing trip plans that align with the forecast is such a key part to success in the mountains. I hope that my readers have learned a thing or two and most importantly, become inspired to practice this craft with greater precision, analysis, and dedication.

Once again thanks,as a long time weather, avalanche subject nerd you’ve done a great job here. I feel (recent observation) on the nwac site is great local area info and general whats happening out there info. Thanks Kyle!

You are welcome! I am happy people have gotten use from this.