Table of Contents

The Most Wonderful Time of the Year

For many Pacific Northwest skiers, spring is the best time of year. The snowpack stabilizes, weather improves, access roads melt out, and the alpine beckons. Spring skiing is incredibly exciting and freeing, but there are a different set of rules that govern decisions. In this post, I explain my process for planning spring skiing, from where and when to go to what to ski.

What is Spring Skiing?

To me, spring skiing is not just skiing in the spring. Spring skiing means adventure, rapidly changing conditions, corn snow, and getting deep into mountains. In general, I consider spring skiing any ski trip where most of these elements are present:

- There is an expectation of skiing “corn snow” at some point.

- You are starting at or below snow line.

- Your access point is not a common winter access point, meaning it is harder to get up to date conditions.

- Access conditions change rapidly day to day and even minute to minute.

- The sun is the primary driver of avalanche danger.

What Makes for Good Spring Skiing Conditions?

Most spring skiers seek “corn” snow. Corn snow is found when the surface snow goes through freeze-thaw cycles, transforming from dry snow grains to melt freeze grains. As the top layer of snow warms after a solid freeze, it softens just the right amount, making for effortless turns on top of a firm base. The snow grains might even resemble corn, which is where the term comes from. Good corn is probably the easiest snow to ski in the backcountry.

Powder is not impossible to ski in the spring and oftentimes we can find preserved powder all the way into late May on steep, high elevation north aspects. But most spring skiing in the PNW is focused on corn snow.

Like finding good powder, there is not a magic formula to predicting corn snow. But there are some general trends to look for.

Good corn skiing starts with a consolidated base.

Granite Mountain on the I90 Corridor might be the most reliable corn farm. Why? Because the winds strip the south face, resulting in a rather shallow and consolidated snowpack all winter. In the spring, lower elevations and solar aspects tend to consolidate faster due to warmer temperatures and a shallower snowpack. These slopes are quicker to provide the supportable base needed for corn. It’s not that good spring skiing is impossible to find before the underlying snowpack has consolidated, but the time window on a given day for good spring skiing will be much shorter and harder to nail if the base has not consolidated. It can quickly transition from crust to deep mank and create dangerous avalanche conditions.

Corn Snow takes successive freeze-thaw cycles to “mature”.

You have probably skied sun warmed snow in the winter and found it grabby, mushy and unenjoyable. It might freeze overnight, developing a crust, and be similarly bad the next day once the sun hits it. At what point does it become corn? It can take many days to weeks, and that is why corn is not as reliably found until April and later when warmer ambient temperatures and stronger solar input can consolidate the snow down to melt grains. The exception is after certain winter rain events, when corn can be found because the rain essentially speeds up the consolidation process. The best corn comes after multiple straight days of sunny, warm days and cool, clear nights – a “corn cycle”.

An overnight freeze is critical.

Corn snow is best right as it softens the critical amount. If the snow does not freeze overnight, then it might be too soft already in the morning. In addition to poor skiing, this can also result in greater avalanche danger. The surface snow can refreeze even when overnight temperatures are above freezing as long as it is clear overnight. In fact, I find that cloud cover, not freezing levels, is the most important predictor of an overnight freeze.

Fresh snow can “reset” the “corn cycle”.

Once we are looking for corn skiing, fresh powder is usually unwanted. A fresh foot of snow might take a few days to a week “burn down” into consolidated melt grains. In the meantime, it can feel mushy or like breakable crust. When this happens, I often look for areas that received less fresh snow, or terrain features that were wind stripped during the storm. On the other hand, a dusting to a few inches can smooth out the snow surface nicely and typically will “corn up” in a day or two.

Follow the sun.

Assuming a good overnight freeze, and reasonable day time temperatures, the sun will break down slopes and create good skiing conditions. Eastern slopes corn up first, followed by south, and west. At some point in the day, lower to moderate angled north slopes might also, depending on ambient temperatures and the overall snowpack. Wind and clouds delay the maturation of corn. There is no magic way to estimate the precise time, as that depends on the temperatures and snowpack.

A mature snowpack will have a longer window for corn.

As I said earlier, it is not impossible to ski some corn-like snow in mid February after a week of freeze thaw, but the actual window of good skiing between breakable crust and mashed potatoes might be very slight. The deeper we get into the spring skiing season, the longer “corn o’clock” tends to last – until, of course, the slopes are entirely melted out or just sun cupped. Patience is important. That is why I usually wait until later in the spring for big traverses that require traveling on many aspects at different times of day. Earlier in the spring, it is easier to go for single-line objectives that require less complicated timing. A big snow year will give more time for a snowpack to mature before completely disappearing. The deep snowpack of the PNW, especially in the northwestern Cascades and volcanoes, is why it is known for spring skiing.

For weather nerds, check out my series about Weather in the Cascades.

Deciding When To Go

Now that we have covered what makes good spring ski conditions, we can apply that knowledge to a few critical questions that can indicate when conditions will be good.

Is the snowpack consolidated enough?

If I am attempting a “spring-like” trip, then the first consideration is if the snowpack has reached a “spring-like” state. This means that the snow is generally consolidated and so once it gets warm and sunny, it will hopefully not be mashed potatoes. This also means that any weak layers deeper in the snowpack have healed and so avalanche concerns are only in the surface snow (you might hear the term “isothermal” which means constant temperature throughout the snowpack). NWAC often talks about how “wintery” or “spring” a snowpack seems in April, and you can gather this information yourself by digging and investigating the snow grains and layers.

Consolidation can happen at varying times depending on the location and year. Generally, the snowpack consolidates faster in the southern and eastern regions of the Cascades because the spring weather is usually warmer and drier and the snowpack shallower. The northwestern Cascades and high elevation volcanoes take the longest to transition, but also usually have the deepest snowpack so they melt out the latest. South and west aspects consolidate faster than north aspects. I tend to plan my trips with this in mind, seeking corn earlier in the Teanaway, Stuart Range, or eastside before moving gradually north and west. The Olympics are similar, although the northeast Olympics actually have the thinnest snowpack.

Has it snowed recently?

Once you are seeking spring skiing, new snow is a nuisance. An inch or two usually turns to corn after a day or two of sun, but a bigger late spring storm can mess up an otherwise consolidated snowpack for longer. Skinning from wet spring snow onto cold dry snow also produces heinous glopping on your skins. There might be a brief window to try to ski this fresh snow as powder on north aspects. If this is something you are dealing with, look for areas that got less fresh snow or aspects where the wind stripped more of the fresh.

Will the snow surface freeze overnight?

As discussed earlier, good spring skiing is dependent on an overnight freeze. Although temperatures should be monitored, the most important factor is cloud cover. If it is clear overnight, the snow surface will almost certainly refreeze in the alpine, even if “freezing levels” are higher than the elevation. If it is cloudy, you might not get a refreeze. This is because clouds prevent the snow from radiating heat into the atmosphere. There are differing levels of refreezes. A slight refreeze will break down quickly once the sun hits it. A strong refreeze might take most of the day to turn to corn. Guessing when crusts will break down to corn just takes experience.

Will the snow soften during the day?

There are days when the snow surface might never soften. Wind, clouds, and cold all delay the breakdown of an overnight freeze. Generally, if temperatures are at least around freezing, the sun will break down any crusts at some point as long as it is not super windy. When it is cloudy, or for northern aspects, you can still get corn from ambient temperatures or indirect sunlight, but it might not be as predictable.

Has it gotten this warm yet this season?

Anytime the forecast is calling for a new high temperature of the year, you should be a little wary. Especially in early spring, these big warm ups can lead to “spring shed” events where the snowpack goes under a lot of warming stress and larger avalanches are possible. If I still want to get out during these big heat events, I will start early and limit my exposure to avalanche slopes and cornices throughout the heat of the day.

Deciding Where To Go

So you have identified good conditions, but how do you know what terrain you can access? This is the adventurous part of spring skiing!

Where can I drive to?

This is such an important question. Many spring tours are dependent on driving up unplowed forest roads. If you guess wrong, you might have an additional five miles of patchy road to walk and skin. Sometimes roads are washed out in the spring.

These are a few methods I use to figure out what is drivable:

- Facebook groups such as Pacific Northwest Mountaineers, PNW Peak Baggers, and Turns All Year can have valuable information. You can search these groups.

- Check online forums like TAY.com, Cascade Climbers, and NWHikers.net.

- Look at WTA trip reports for any hikes that start from that trailhead.

- NWAC Observations might have relevant information.

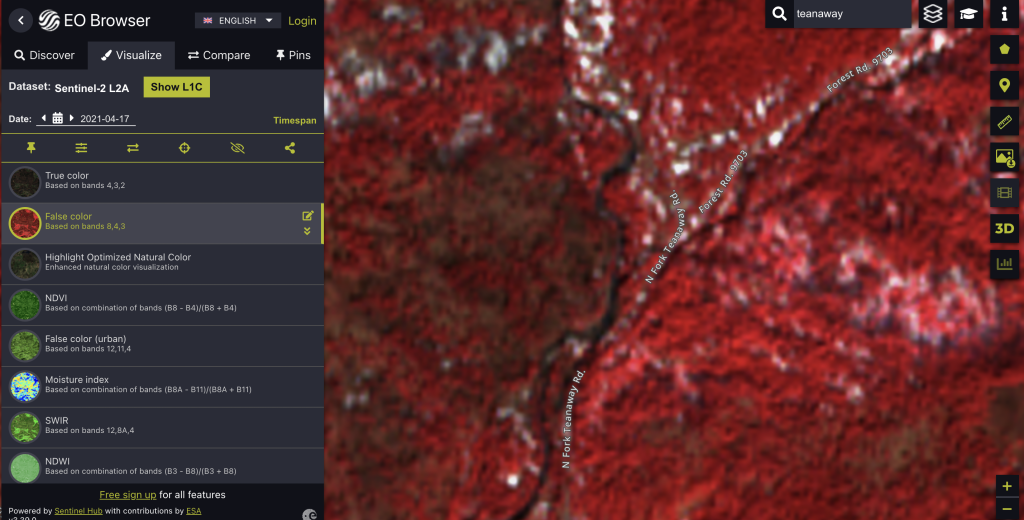

- Use SentinelHub to browse satellite imagery. There might be recent clear imagery where you can see snow coverage on the road.

- Call the district ranger to see if they have any updates.

There are certain characteristics that make for “good” spring roads:

- A road that rapidly gains elevation means that the precise melt out point makes less of a difference to the overall trip length. They are also less likely to have long dry patches after a blocking snowbank.

- Be wary of shaded or northerly sections that might hold snow even when higher sections are dry.

When I am unsure of road status, I like to drive out the night before to see how far I can get. That way, I know what time I should start in the morning. Always have a backup plan if the road is closed or impassable. I carry a chainsaw, shovel, and tow strap with me on these sorts of trips. A high clearance vehicle is helpful. When in doubt, be cautious with driving through spring snow. What might be firm and supportable in the morning could be impassable mush later in the day.

Where is snow line?

Snow line is important. For example, for Glacier Peak, you probably want to wait until snow line is at 4k or above because then the valley approach trail will be entirely snow free rather than annoying skis on / skis off. For Eldorado, the approach is easiest when the steep forest (2k-3.5k) is dry, but the boulder field is covered (which is between 4k and 5k). Each tour tends to have an ideal setup. Think critically about the proper melt-out timing for your tour.

Like the previous question, forums, groups, and SentinelHub are your friends. The USFS snow depth map gives rough snow depth estimates. Generally, snow line is pretty consistent across the same aspects in a given zone, so reports from nearby tours can be helpful.

Where are conditions good?

As the previous section explains, there are many variables in predicting good conditions. If you are flexible and patient, you can often find good spring conditions somewhere in the Cascades!

Planning a Tour

I know I have covered so many topics already – where and when. But how do you plan the actual tour?

There are tons of resources out there for common spring tours. The Volken Guide has many great tours. You can browse TAY and various blogs for inspiration. Maybe there is a peak that inspires you. The opportunities are truly limitless.

I have a few resources on my website that could be helpful:

- Washington High Routes and Traverses: this list has many ski traverses, which are colored blue.

- Spring Skiing Tagged Posts: You can find a few dozen of my spring skiing trip reports here.

If you are looking to create your own tour, or just dial in the planning for an existing tour, then here are a few concepts that might be helpful.

Follow the sun

During the spring, east aspects corn up first, followed by south, west, and possibly north. Descending a west aspect in the morning might be icy, and an east aspect in the late afternoon or evening might be refreezing breakable crust. So an ideal tour might descend east aspects earlier in the day, south aspects later in the morning, and west or north aspects in the afternoon. An example of this clock-like movement is the Bean Creek Ski Circuit. If you are in a bowl with all of these aspects available, then you have a tour plan! If you are doing a loop, consider which direction would work better with the sun. Not only might being on a steep southeast aspect late in the day be unpleasant – it could be downright dangerous!

When in doubt, be early

You can always wait at the top of a line for corn, but if you are late it could be potentially unsafe or just unpleasant. So if you are unsure when the line will soften, it is best to be on the early side and bring some warm clothes to wait.

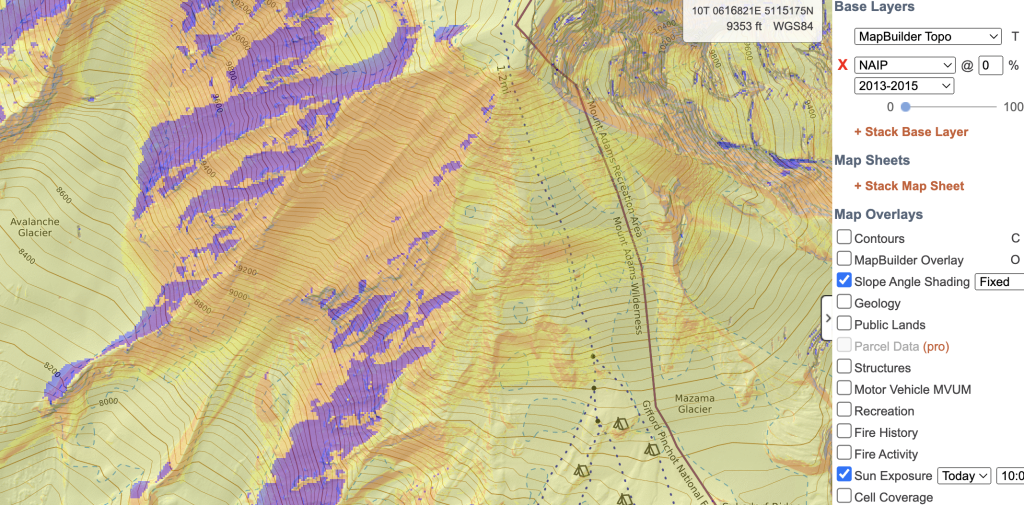

There are a few tools for seeing sun exposure throughout the day. The caltopo sun exposure layer is very helpful for seeing when an aspect first gets sun. The new app Backtrack has a much cleaner and more performant sun shading layer, but that feature is currently only available on iOS. You can use that and a knowledge of temperatures and winds to guess when the corn will be ripe. Note that couloirs or deeply inset features will corn up slightly later than an open face on the same aspect.

Steep approach and exit trails are your friend

If hiking is involved (as opposed to skinning from the car) the easiest spring approaches are usually steep trails. This is because it diminishes the distance you have to cover in patchy snow. Ascending elevation quickly, you can be from dry trail to a deep spring snowpack in only 500-1000 vertical feet. This also means that you do not have to nail the timing of the melt out as precisely. The same is true for exits.

If your approach or exit does not use a trail, you probably want to go earlier in the season where there is snow coverage down to the access road. If that is not possible, then steepish (but not too steep) terrain is still your friend because it will diminish the amount of time spent in that zone where there is not quite enough snow to ski but plenty of snow to posthole.

Using a trail for the approach also means that it is easier to start your trip in the dark, as is often required for spring objectives.

North aspects hold snow much longer

This means that the best exits are typically north facing because you will be able to ski lower. Additionally, the snow will not be as mushy late in the day on a north aspect. This is not a hard rule, but it usually will be more “efficient” to exit to the north.

Be wary of firm slopes

As you are probably skiing more consequential lines in the spring, firm conditions can be very dicey, both to ascend and ski. Think carefully about when/if slopes will soften to avoid having to sideslip your way down a scary, icy couloir. Make sure you have your sharp things (crampons + ice ax) with you and put them to use before you actually need them, not mid-slope when you are sketched out!

Watch out for creek holes

It feels like every few years someone dies falling through the snow into a raging creek below. Be careful crossing depressions or gullies later in the day when the snow has softened. In some cases, you will hear running water beneath, but danger can lurk even when you cannot hear anything. When planning a tour, think carefully about what time of you day you will be crossing creeks and where you can expect to be able to cross.

Shorter runs typically mean better snow

While a 4000 foot descent might be enticing, it is unlikely you will get great conditions from top to bottom. If you want the lower to be corn, you probably will have to accept firm conditions up high. The exception is large concave slopes like the SW Chutes of Adams, where it truly is possible to get good corn top to bottom. But with most tours, there is usually not much sense in skiing runs longer than a few thousand feet. Your energy is better spent skiing multiple lines, changing aspects with the sun.

Use aspects to quicken the transition to snow

An ideal setup could be a south facing trail that curves around to a north facing basin that suddenly has deep snow coverage. Leveraging terrain that works to your advantage like this can make the transition from hiking to skinning or skiing to hiking much easier. For example, with Vesper Peak, you can go from completely dry trail to a shaded north facing Wirtz Basin that has deep snow coverage. The transition is easy and perfect in late spring.

The more options the better

If you are not keen on a specific objective, you might find the best conditions when a tour has multiple aspects and elevations to play on. The best spots have bowls that gradually change aspect, so you can fine tune the aspect to where the best snow is at the moment.

Be reasonable about your commitment level

It is one thing to skin up a road or valley trail, try to ski some corn on some moderate slopes, and exit out at any point if the conditions are bad. It is an entirely different thing to embark on a giant traverse or linkup that requires traveling on many aspects at different times of the day, with few options to bail. You have to be honest with yourself about your experience level and how committing of a trip you should embark on. If you are unfamiliar with predicting spring conditions, it is best to ease into things.

If the weather or snowpack is uncertain, I often opt for less committing spring tours. This does not mean you cannot explore a new zone or have a great time. Last May, after many late season storms and cloudy weather, I went out for a WA Pass day with no real objective, but a variety of options. In the end, we ended up skiing some nice psuedo-corn and even steep north facing psuedo-powder in the North Couloir of Big Kangaroo. A flexible tour plan with many different aspects and options allowed us to scavenge a doubtful forecast into an awesome day of skiing.

Sometimes the objective is more important than ski quality

Most of this guide is about finding good spring snow. And even if you have an objective, it is nice to get it in good conditions. But sometimes, you might have an objective where it simply is not possible to get good conditions on most of your runs, and that is fine! Little T and Big T in a day was definitely an example of that. But it is still important to consider the safety and viability of your plan.

Special Gear for Spring Skiing

Here are just a few of my thoughts for the equipment needed for spring skiing that might differ from normal winter tours:

- Lightweight skis, bindings, and boots: Usually 80-100mm underfoot, possibly slightly shorter than normal. Weight depends on your priorities. Sharp edges are helpful. With lighter skis, you can also get by with lighter boots and minimal bindings.

- Boot crampons and ice axe: Aluminum crampons are the lightest, but you might want steel if you anticipate really firm conditions or mixed scrambling. A short ax (45-50cm) is best because if you are using an ax, it is probably quite steep. Some people like whippets for steep skinning and skiing.

- Ski crampons: Theoretically, if the snowpack is completely consolidated, then you should just be able to boot if conditions are so icy you cannot skin. But earlier in the spring, it might be icy but not boot supportable so ski crampons can be helpful. It depends on the objective and my partners if I bring them or not.

- Skin wax + extra pair of skins: Glopping can happen when there is a mix of dry snow and wet snow, so skin wax can be essential. I often hot wax my skins the night before to help with this. In a larger group, I will often carry one extra pair of skins because wet conditions can cause glue failure. You know your skins and how reliable they are.

- Ski scraper: Unfortunately spring can mean pollen on your bases. Having a ski scraper can at least salvage some of your glide if you are unlucky.

- Repair kit: Spring ski tours are often long and committing. Be sure to have a good ski repair kit with duct tape, voile straps, glue or epoxy, para-cord, and a binding tool at the least.

- Extra pair of sunglasses: If someone forgets their sunnies or breaks them, it could be a disaster without a backup pair.

- Sunscreen and SPF Lip Balm: The combination of strong sun, snow, and high altitude makes sunburns at this time of year the most vicious. I recommend using SPF Lip Balm because lip burns are the worst (except, maybe, the roof of your mouth). Highly recommend wearing a hat and sun hoody also.

- Showa Temres 281: These are like the iconic 282s, but with no insulation. So they’re basically dishwashing gloves. They are helpful for handling wet gear or climbing snow when it is too hot for the insulated Showas. You can size up if you want the option to wear a liner glove underneath, and now you have a flexible, ultralight, ultracheap glove system.

- Carabiner: Even if you don’t have technical gear, a single carabiner connected to a pole strap and a water bottle makes it easy to fish for fresh water deep in cracks or holes in the snow.

- Glacier Gear: If your route involves glaciers, you will need to decide whether to bring glacier gear or not. If in doubt, bring it. It pays to have an ultralight harness, thin glacier rope, and rescue gear.

- Lightweight approach shoes: If you are doing a traverse and have to carry your shoes with you, then weight matters! If not, it does not. Usually I like to use a real old pair since sometimes animals will chew on your shoes if you leave them hanging from a tree or next to a trail.

Other Resources

There are some other great resources out there:

- Lowell Skoog, the father of Cascade ski traverses, has an entire series on planning ski traverses in the Cascades.

- Kyle Miller has a great repertoire of spring routes.

- Jason Hummel has so many great spring trips and stories.

Plus, there’s this beautiful video.

Springing Into Action

Spring is a special time for backcountry skiers in the PNW. Spring ski mountaineering is what convinced me to learn to ski in the first place, and it has remained possibly my favorite part of the season (although I also love powder). There are a lot of lessons in this guide and it will take time to be able to apply all of them. The best thing you can do is make plans, have experiences, and reflect thoughtfully on what went well and what did not go so well. After all, the process of growth and adventure is the biggest reward of all, bigger than any objective.

Incredibly helpful information, thank you!