Table of Contents

The Story of Sloan

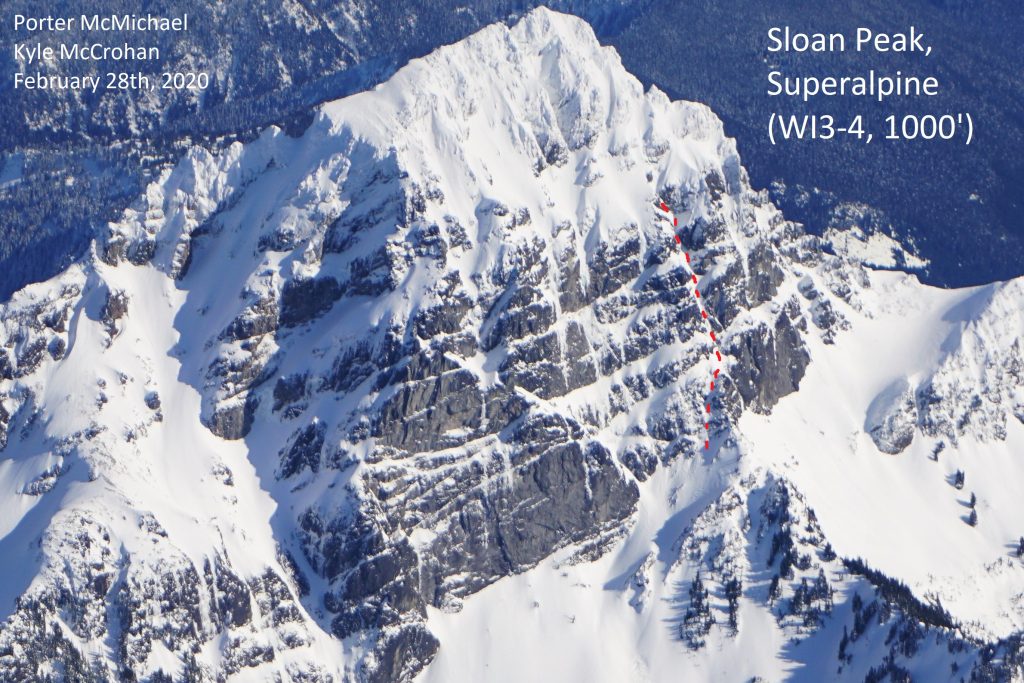

On February 28th, 2020, Porter McMichael and I made what we believe to be the first winter ascent of the West Face of Sloan Peak. We climbed an incredible line approximately 1000 ft long of WI3-4 and steep snow climbing before our route joined the final 600 ft of snowfields to the summit. On the very final ice step, I suffered a long fall and broke a few bones in the right side of my face. We bailed down the route and skied out.

The west face of Sloan is perhaps the most aesthetic winter face in the entire North Cascades, with countless unclimbed lines of world class quality and technicality. I hope others can learn from our experience and build on it. For the entire story of Sloan (for route beta, skip to the end), read on.

Prologue

To fully understand my relationship with Sloan, you have to go back many years. I wasn’t an avid mountaineer growing up, just going on a few family hikes each summer. Although sometimes we would do classics on the I90 corridor, we often went to the Mountain Loop Highway. We visited the Big Four Ice Caves almost every summer since I was little. I remember biking into the ghost town of Monte Cristo and sitting on the railway turntable as my dad pushed me around. When I got older, we started doing hikes like Pilchuck and Dickerman. As I started to really fall in love with the mountains after finishing high school, my friends and I cut our teeth on the local peaks like Pugh, Del Campo, Vesper, and Forgotten.

It is impossible to travel in this area and not take notice of Sloan Peak. Sloan dominates the West-Central Cascades with prominence only equaled by a few other non-volcanic peaks like Stuart, Shuksan, and Bonanza. The darkened west face and sharpened summit ridge reminds one of the Matterhorn. Even before I knew what was required to climb Sloan, I knew I wanted to climb that mountain. Looking back, I realize that the mountains we see frequently mean so much more to us than some random peak far away. They become almost personified, and Sloan would turn out to have quite the personality.

A few years later, after learning the basics of glacier travel, I attempted Sloan with Chris and Kenny from the North Fork Sauk River side. It was mid June, and the river was a death trap. An embankment completely eroded beneath my feet and I was swept into river, pinned against a log in the rushing water. Luckily I managed to slide my way out of the strongest flow and keep my head above water. It was the scariest thing that had happened to me in the mountains – at the time, at least.

Another few years passed and I became distracted by the sensual spires of the Stuart Range or the giants of the Cascade River Road. I learned to rock climb, ski, and even ice climb. There are so many adventures to be had in the Cascades that it was easy to forget about the Mountain Loop.

One warm January day last winter, Jacob and I set out into the Snoqualmie Backcountry and made the first recorded ascent of a 4 pitch ice route on Bryant Peak. There were many incredible aspects about that experience, but the biggest one was simply how easy it was: we didn’t have to go far, we didn’t need perfect conditions, we didn’t need a snowmobile, we didn’t even have to be good climbers. Really, it was an eye-opening experience. As Washington Ice Climbers, we are inundated with this false narrative that there is no good ice climbing in our state. We surrender in defeat before even trying. It took this experience to allow me to see through the lies and realize that the North Cascades are a gold mine of under explored alpine ice climbs. We spend 99% of our time in the winter recreating in just 1% of our vast mountains. What secrets could the other 99% hold?

After our climb on Bryant Peak, I caught the bug and started hunting the internet for Washington Ice. And, for the first time in years, I returned my attention to the Mountain Loop. It seemed every major peak – Whitehorse, Whitechuck, Three Fingers, Sperry – had some massive WI4 alpine route put up in the 2000s by Dave Burdick, Colin Haley, and the other great Cascade hardmen of that generation. But just like that, those climbs disappeared into the anals of CascadeClimbers.com and the hordes returned to Chair Peak to climb some snow route that had 20 ft of WI3. Somewhere in my research, I stumbled upon John Scurlock’s photos of the West Face of Sloan Peak, the mightiest of all. As I stared at the Canadian-Rockies-esque ice pillars lining the face, I felt like I had just discovered that Santa was real; yes, Washington has real ice! I spent hours researching, but could never even find an account of an attempt on the face (except the route Full Moon Fever, which climbs the NW Face). It seemed too good to be true: year round access, relatively short approach, dreamy lines. Why hadn’t it seen any action? It had to be home to the greatest unclimbed ice routes in Washington (that people know of, at least). Like a seed, curiosity began to grow in my mind. Someday, I vowed, I would answer this question.

Jacob moved to Corvallis after the summer and I had to find a new ice partner. I was watching this young Western Washington University student named Porter send some rad alpine ice routes during the fall in between collegiate cross country races, so I decided to message him. The next week, we climbed the NE Couloir of Dragontail together and a partnership was found. I sold him on Sloan that day.

Based on photos, aspects, and elevation, we figured that the optimal window for this climb was January through Mid March. But January came and went without a day of sunshine. It was storming incessantly and ice conditions were very poor. Still, we agreed that given the first cold high pressure window, we would give it a go. Our bodies were floating through powder, but our minds were frozen on Sloan. Mid February rolled around, and a weather window arrived. We knew we likely wouldn’t succeed on our first attempt; we didn’t even know if there was ice to climb. But you’ll never know if you never go.

Attempt One

We met up in Arlington the evening before and drove out to Darrington. I had done a bit of research to figure out that the Mountain Loop, despite all the rain we’ve had, had not washed out and was drivable to the Bedal Creek gate. There were many potholes, but thankfully others had come through and removed downed trees take make a passage. We stopped about a half mile short of forest service road 4096 and went to bed.

We woke up early the next morning and were skinning from the car (barely) a little after 3 am. Road 4096 had quite a few downed trees, necessitating some skinning magic or just simple crawling.

The powder got deep pretty quickly and our progress was slow on skinny skis. I always struggle with dark starts, but I was really in a fog this time. My gut felt sick and it was hard to move forward. Every part of me wanted to be back in bed. Eventually, near the end of the road, we decided to turn around. We both needed to be 100% to pull this off, and neither of us were. I’ve never had such a bad crash at the start of a trip, and this was the trip I had been waiting for for so long! But that’s how it goes sometimes. It was my second attempt at Sloan, and I still had never got more than a few miles from the car.

I crashed when I got home in the morning and slept for a good 18 of the next 24 hours and still felt sick and exhausted. Porter got sick over the next few days too. It was pretty frustrating watching the nicest weather and snow all season go by and being stuck at home. But this is the fate of an explorer: to fail is just part of the reason why it feels so good when you finally succeed. I often question myself, asking why I don’t I just follow the crowds, go ski easy powder and do the sure thing? But deep down, I’ve always known the answer.

An Eye in the Sky

The next day, I got an unexpected text from my brother-in-law, Shane. I had casually mentioned to his father that if he ever got the chance to fly by Sloan on a clear day, please snap me photos of the west face. Shane and his father had done exactly that, and Shane shared with me a bunch of photos from their aerial reconnaissance! Thanks, guys!

In general, the mountain looked very wintry still. In most cases, the ice actually looked fatter than in Sculock’s photos! However, when we zoomed in, it appeared the bottom of one key pillar was not fully touching down! It was difficult to tell for sure, but it didn’t look good. We evaluated other route options and came up with a bunch of different lines depending on what we actually found.

As we looked at the all the different angles, it became more and more apparent how incredibly steep and big some of the flows were. There were multiple free hanging pillars at least 100 ft in length. Our original planned route that stepped up the middle of the face was beginning to look like a pipe dream; we are not WI6/M6 climbers. So we agreed to prioritize a steep weakness on the right side of the face, possibly the only viable way up the face under WI5. It seemed like a continuous moderate steepness and something that was within our wheelhouse.

In a little way, these photos felt like validation of this pursuit. I wasn’t crazy for thinking there was good ice up there. Even in a bad ice season, the face was loaded like a gold mine. I’ve never seen anything else like it in Washington, not even Colfax Peak could compare.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized how challenging it was to get this face in the right conditions, despite the abundant ice. The approach starts low and requires a lot of schwakery and trail breaking. The face gets lots of afternoon sun, especially by March, so the lines likely don’t stay in past astronomical winter. The sun also creates overhead hazard if on route in the afternoon. The difference between the ascent and descent lines necessitates a lot of booting in deep, heavy Cascade snow. Ideal conditions would be a warm up followed by a hard freeze and high pressure, but we just haven’t gotten that much this winter, for better or for worse.

Attempt Two

Porter ended up getting sick also (likely from me), but the photos from Shane and his father had gotten us excited for another attempt on Sloan. At the end of the next week, there were a few days of high pressure and stable snow. Freezing levels were a little high – about 5,500 ft during the day and 3,500 ft at night – and a storm was timed to hit about 4 pm, but we felt like we could get in and get out quickly enough to do it safely. I talked with some meteorologists the day before (benefits of working at a weather science company) and confirmed that there was high certainty of the weather and visibility holding off until late afternoon. It wasn’t the perfect window, but perfection is tough to find in the Western Cascades.

We left the car around 2 am and had to hike about a half mile before skinning, as road 4096 had melted out considerably in the last week.

There was another reason why this was a good window to make an attempt: our buddy Steve had set a skin track the previous day most of the way out to the west face! Steve is another adventurous local who loves breaking trail, exploring, and bushwhacking. He gave us helpful instructions like “when the skintrack diverges, take the higher one”. The skintrack allowed us to save so much time, energy, and focus on the approach. Thanks so much, Steve!

Coverage still wasn’t great as we left the road and began to follow the trail at 2700 ft. There were a few open creek crossings.

It was generally pretty cruiser until we diverged from Steve’s skintrack around 3700 ft. Steve had ascended the slope to the east to get onto the glacier on the northeast side, but we wanted to continue up Bedal Creek. We briefly got turned around and crossed Bedal Creek in the darkness, but then we corrected and ascended surprisingly open terrain between the two branches of the creek.

As we got higher, we entered a creek drainage that was strangely wide. As we got higher, it became more obvious we were in a massive avalanche chute that ran to the valley floor. It was scoured so deep that the walls resembled a terminal moraine, containing us, so we continued upwards.

In the faint early morning light, the massive cliffs of Sloan began to loom closer. We realized that we were nearing the start of Full Moon Fever. In the darkness, huge ghostly white streaks rolled off the mountain. Darkness has a way of obscuring size, but we knew we were in the presence of massive ice flows.

Luckily, the chute opened up and we were able to traverse right out of it. We skinned across supportable crust underneath the gargantuan west face, aiming for the saddle on the spur ridge west of Sloan, the headwaters of Bedal Creek.

Slowly, light grew from the east. We could see straight down to the flickering lights of Darrington. But our immediate attention was the biblical west face of Sloan, the reason we were here in the first place. It towered over us like few other walls I’ve seen. And with each passing minute, we saw with greater clarity the wicked ice pillars hanging from the face: hundreds of feet long, free hanging, immense. It was like the Winter Dance of Washington. Nothing we’ve ever seen could compare.

In the faint darkness, we could begin to make out our line, and it looked promising. The gully looked absolutely fat and rambly – ideal. However, we knew that getting into the gully would be perhaps the greatest technical challenge.

At the 5700 ft ridge, we discussed whether or not to leave skis here. We knew that booting in this soft, mushy snow would be terrible. Carrying skis over limited our technical abilities, but gave us many more descent options (like descending off to the north across the glacier). We agreed to carry skis. We were trying to keep things mostly around WI3 anyways.

We skinned up the ridge, then booted. The ridge was more complex than expected, and we lost some time weaving between cliffs.

It was a beautiful morning in one of the truly beautiful parts of the Cascades.

As we got higher on the ridge, we had to make a decision about how we were going to approach the ice gully. To the right, there appeared to be a steep ice flow, but it looked delaminated and sun affected. There might have been an easier flow on a ramp out of view, but we didn’t bother to explore.

As we traversed to the left side of the ridge, we found a nice looking ice flow that would grant us access to the ice gully. We actually had to downclimb a bit to the start of the pitch.

We racked up, and then Porter was off.

The first pitch had some rambly ice that led to a solid 25 ft near vertical curtain. Maybe we’re just weak climbers, but it felt like a decent WI4. At least the ice felt solid. Turns out it would be the hardest pitch we climbed all day.

There was a second little ice step and then we walked up the ridge to the base of the gully.

While Porter was top belaying me, he had noticed periodic bursts of spindrift coming down the gully, but nothing sizeable. It was windy up high, likely contributing to the spindrift.

There were a few options to get into the gully. I started on the left side, climbing a section of fat 80-85 degree ice. I was able to chimney my feet on some rock behind to get rests.

Above the initial step, I continued up even fatter WI3 rambly steps. The pitch was incredible – it just kept giving and giving. It is the type of climbing you dream of as a weak alpine climber like me.

It was nearly a full 60m pitch, and most of that was solid ice climbing! Incredible! We were totally stoked with how well the climb was going, better than even in our wildest dreams. It reminded us of the NW Couloir of Eldorado, but more technical and sustained. High quality moderate climbing in a completely wild setting; it felt totally alpine, it felt superalpine.

We both remarked how incredible it was to be in the year 2020, within sight of a metropolis of millions, and to still have wild places like this. It doesn’t have to be some huge alpine face – it could be a lonely meadow, an unspoiled tarn, or sweet ski line, whatever makes you tick. For us, Sloan was never about ego; it was just about curiosity and the desire to unlock the secrets of the places that inspire us. Everyone has their own Sloan, if they allow themselves to be inspired.

The sunny slopes beneath were a visceral reminder that we needed to continue to move efficiently. We did not want to be in this gully when the sun begins hit the upper west face around 11 am. So Porter led off quickly on slightly easier terrain, and I followed simul climbing.

This pitch was probably over 100m. As we regrouped at Porter’s next anchor, we knew we were likely just one pitch away from finishing the technical portion of the route and entering the upper snowfields.

I climbed a short step before opening to a wider snowfield. To my left, there was a snow ramp the cut above some cliffs. Was this the snow ramp that we wanted to take? Honestly, I had not done a great job of keeping track of where we were in the beta photo, but it looked right. However, directly above me, there was another little WI3 step. Beyond that, it looked to mellow out. Taking the snow ramp looked exposed and unprotectable. Continuing upwards seemed more direct, fun, and protectable, so I took that option.

As I approached the final curtain, the ice seemed different here. I was having a good time getting a screw to bite into the ice. The curtain appeared steeper than previously, dead vertical for a body length. I tentatively poked around, trying to figure out where the top out would be best, if I could get any more screws in, if I should downclimb. Out left was least steep, but it was just thin ice over rocks. I waffled back and forth, wasting energy.

Eventually, I decided to tackle the curtain in the center where the ice looked best. “Just a few more moves”, I thought to myself. We’ve all been there: in a slightly sketchy spot, looking upwards to safety. I got my sticks above the bulge and pulled my head above, only to see flat powdery snow – the worst possible topout! Below, I was kicking my feet in hard, but this only broke through the entire outer layer of ice to some rotten snice beneath, putting me in a completely overhung spot. I knew I was in a bad spot. I couldn’t pull the topout without good sticks, downclimbing was near impossible since my feet were destroying the ice, and the pump clock was ticking. I was getting desperate. I tried traversing to the right to get to an easier top out. I clipped into my tools to try to get a rest.

There was a snap, a brief catch, and then more falling. The next thing I remember is lying in the snowfield far beneath Porter and the belay. Apparently I stood up quickly asked him “where are we?” nearly a dozen times.

I looked up and began to puzzle out what happened. I had fallen a long ways, likely 200-300 ft. One glove was missing, as was one of my tools, due to a snapped umbillical. This part is all still slightly fuzzy to me. Porter had already made a V Thread and was rappelling down to me. He explained to me what happened. My ice screw had pulled out and I tumbled down a series of snowfields and ice steps. Then he checked me out. It seemed that I had all of my motor capacities, which was critical. Porter told me I had been unconscious for about 5 minutes and he had already activated the SOS button on his inReach.

I was pretty dazed, but was still able to rappel myself down the gully. I was pretty useless, but Porter did a great job setting up V-threads in the ice to get us down the gully. Miraculously, the mountains gods had pity on us and no spindrift bombed us during the descent, even though sun was on the upper mountain.

Even though I wasn’t thinking super clearly, I had enough capacity to realize that our main concern was exposure with the incoming storm and potential increased Intracranial Pressure. I had blacked out, which meant that my condition could potentially deteriorate to increased ICP. The key sign to monitor was repeated vomiting. I felt nauseous, but wasn’t vomiting.

Once we were out of the gully, we made two more raps off dead snags to get down the first pitch and then I booted down snow towards the basin beneath the west face. I felt so relieved to sit down in the snow and just close my eyes. In some ways, the days events still felt so surreal – it was one of the best days of my life, and then suddenly it was one of the worst. Now it just is. Fortune can change so swiftly in the alpine, but in life too. One moment you’re on top, and the next you are deep in the pit. Never take anything for granted.

Porter was handling the communication with the rescue effort and told me the helicopter was coming soon. I felt exhausted, still had a headache, was shivering, and wanted nothing more than to be off the mountain and in a warm bed. But we kept talking to keep ourselves distracted. I’m not sure what time it was, but the weather was still holding off, at least for the moment.

The helicopter arrived and flew over us a few times. Each time the helicopter arrived, the winds picked up. There wasn’t really a flat open area in the basin for it to land, although it circled around trying to find one. Eventually, we got word that it would not be able to land, but a ground crew would be coming in for us.

All the time sitting around had given me enough time to evaluate my condition and regain some focus. My headache was going away, nausea decreasing, and there was nothing immediately life threatening anymore. I began to feel better and felt like I could self evacuate. I put on skis and tested it out. It wasn’t too bad. I told Porter he could call off the rescue.

We skied down the avalanche chute we originally ascended in the darkness. Breakable crust on skinny skis with a head injury combined to some of my worst skiing of the season, but no one saw it. In a way, skiing helped me forget my pain and guilt and slightly enjoy myself again. It was a relief to get back on the skin track on the valley floor and cruise back towards the road. We never needed to put skins on. Thanks again, Steve, for a wonderful skin track.

Right on time, it begin to rain as we slid down the road and finally walked through mud to the car. Now it was just a few miles of road between us and the comforts of civilization. But for me, I knew it was just the start of the road to recovery, whatever it would hold.

Epilogue

Porter drove us out to Arlington, where my dad and brother-in-law had driven up to meet us. I said goodbye to Porter and then my dad took me to the ER that evening. I must have looked really gruesome, because I got quite urgent care at Swedish Edmonds. They did multiple scans and determined that the only real damage was a few broken bones in the right side of my face. The impact basically went straight to my right cheekbone, fracturing the zygomatic arch and some of the other bones connected to my sinuses. Miraculously, I may have even avoided a concussion because I still have not shown any concussion symptoms.

The swelling has been going down steadily and now my face’s shape is relatively back to normal, although my right eye is still super bloodshot. I saw an ophthalmologist and confirmed nothing is wrong with my vision. Unfortunately, pain has been inversely proportional to swelling and I cannot take Ibuprofen, so Tylenol barely cuts it. Eating is a little painful since the broken bones are connected to my mouth, but nothing is wrong with my teeth or jaw itself.

I now have a surgery scheduled in a few weeks and after that, it should be a full recovery. I feel fortunate that the injury is only really cosmetic and nothing permanent happened to my legs, arms, or, most importantly, eyes and brain. I’m hoping to be back for ski mountaineering season in the spring, with some grand traverses planned with Porter and others! In the meantime, hopefully I don’t lose all my fitness and thank god for March Madness!

Finally, there are so many people to thank. Thank you to John Scurlock for sharing photos of the Cascades and inspiring a generation of climbers. Thank you to Shane and his father for their aerial reconnaissance. Thank you to Daniel and Jacob for providing encouragement and route advice before hand. Thank you to Steve for plowing a bomber skin track. Thank you to Porter’s mom for communicating with my family. Thank you to Snohomish County Sheriff and Everett Mountain Rescue for initiating the rescue. Thank you to Swedish Edmonds for quick and attentive care. Thank you to my family for loving me and taking care of me. And most importantly, thank you to Porter for being calm, smart, and supportive through a scary ordeal. You’re the real MVP.

Reflections on the Accident

It is difficult to not look back on this accident with regret and frustration. I hold myself to a high standard and feel so guilty about putting Porter in a tough spot, stressing out my family, and involving search and rescue. Hopefully this incident will make me a wiser and safer climber.

In some accidents, there might be a blatant error, but I feel like in this case, it was a combination of factors. The ice step where I fell looked trivial from afar, but was actually a stout vertical step. I assumed the ice would be the same good quality as found elsewhere on the route, but my guess is that the sun hits this flow more and thus it was rotten underneath. I also underestimated the difficulty of the topout, which was about as bad as it gets. There were many factors – rotten ice, terrible top out, fatigue, heavy pack, poor protection – that combined in a perfect storm to pop me off. No one factor individually would have been a big deal, but the combination was wicked. Multiple yellow flags will equal a red flag in my mind from now on.

One thing that will always haunt me is: why didn’t I take the snow ramp out left? I know I felt like going straight up was the more protectable/safer option in a way, but I also wasn’t 100% that was the correct snow ramp. Looking back, I should have done a better job following along with the beta photo where we were on route. If I was 100% sure, I might have taken that snow ramp.

Like so many accidents I hear about, my fall didn’t happen on some huge crux. It is often on moderate terrain where we go onto auto-pilot and get too comfortable. When we’re in the alpine, the margin for error is always tiny. We cannot let our guard down. True, there’s always some risk, but we have to do our best to minimize that risk via choosing proper conditions, climbing styles, placing protection, etc. It’s all about shifting the odds ever more in our favor. I need to do better.

You could say that I fell victim to the “Head down and send” mentality. I think many of us have been in slightly sketchy situations where we’re mildly uncomfortable, but downclimbing seems annoying, and in just a few more moves, we’ll be safe. So we put away the gear and just send it. And 98% of the time, we end up okay and don’t think much of it. We get incorrect positive feedback from a poor decision. It’s a mental trap we all fall into from time to time. Sometimes, the right decision is the undesirable one: downclimb and find an alternative.

On the bright side, I believe we handled the situation post-fall well. Porter hit the SOS button nearly immediately. Given that I was shortly unconscious, confused, 1000 ft up an alpine wall with a storm moving in, and had potential for increased ICP, I think that was the right choice. We both were carrying SOS devices, which was important because on an alpine climb, one person might not be able to press the button, so their device is useless if you’re separated. The two way messenger was also key in being able to call off the rescue. Two way messengers are critical when things go wrong. I’d call them essential.

We were both pleasantly surprised with how quickly and easily we could bail down the route. I’m a strong advocate of fast and light alpine climbing, but I still understand that I should be able to bail off a route at any point, even the last pitch. Carrying double 60m ropes and being proficient in building V-threads and rap anchors are important skills when getting on big alpine routes.

Finally, I am so thankful for the medical and technical training both Porter and I have for these situations. Both of us are Wilderness First Responders and Porter has additional guide certifications. We were able to quickly identify the life threatening conditions and key symptoms to monitor and assess an evacuation level. This knowledge allowed us to stay calm and feel like we had an understanding of, if not control, of the situation.

Update 03/15/2020

Porter and Tavish Hansen returned to Sloan Peak and climbed Superalpine once again. They took a different variation to start more directly up the ridge on mixed terrain. Porter ultimately sent the final ice pitch where I fell, climbing sub-vertical ice on the right side of the curtain (I had been forced into steeper terrain to the left due to a spindrift waterfall). They reported minimal spindrift this time. From there, they climbed a few hundred feet onto the upper snowfields, but ultimately turned back and rapped the route due to sketchy wind slab avalanche danger. For more details, see Porter’s trip report.

For some lengthy reflection on the accident, the aftermath, and the true meaning of this climb, see my post Life After Sloan.

Update November 2021

I received some criticism for claiming that this climb was a “First Ascent” afterwards. Looking back, I now mostly agree with the critics. I think that, at the time, I was in a very vulnerable place and needed to feel like I had not completely failed. I wanted validation. I was ashamed, guilty, and just disappointed in myself. It felt like I had blown my one opportunity for greatness. I talk more about this in my articles “The Negativity Dance” and “Where do we go from Here?”.

Now, others have helped me realize that this experience was still a great accomplishment – a story about believing in myself, about self rescue, and partnership. What we accomplished was incredible, but it probably was not an FA in the normal sense. And in the months after, a continued dedication to finding goals that inspire me, embracing healing, and being open about my story has been reason to celebrate. I am defined by a single failure. Nor am I defined by a single hobby. Life is complex and diverse. Life is like writing a book, and if one chapter breathes controversy and disappointment, it just makes the entire story deeper and more interesting.

I still regret the decision I made that led to that fall. I really wish I had not fallen, although we probably would have turned back before the summit with the warming conditions anyways. I really wish I had not botched it. But I am proud of how I have responded over the last two years and know that there is so much more to come.

Route Beta

Despite our unfortunate ending to this tale, I think our route Superalpine (WI3-4, 1000′) is a truly incredible alpine route and I hope others can someday enjoy it and finish it. The setting on the wild west face of Sloan is as grand as it gets in the North Cascades. It feels like the massive pillars of Hyalite or Cody have been transplanted into the alpine here. However, our route is distinctly moderate and accessible. Beyond the first pitch, we climbed nothing harder than WI3. In many ways, it felt too good to be true.

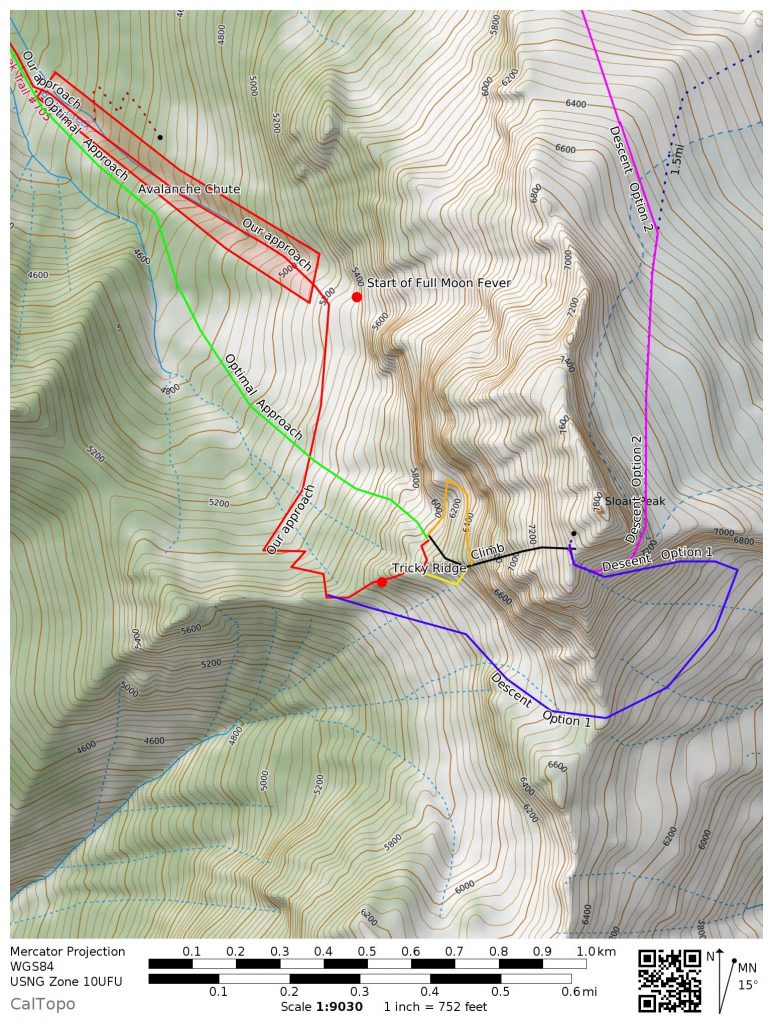

Access up the Mountain Loop Highway is generally fine all winter. It is not gated, and usually enough people drive it that the snow is manageable with a 4wd. Forest road 4096 is generally easy to skin with some blowdowns. The trail entrance is marked and the skinning is pretty easy up the valley as long as snow coverage is decent above 2700′. Above 3700′, where you begin climbing more significantly, travel becomes very easy, although we got funneled into an avalanche chute, which was okay but it might be safer to avoid by staying just further right. Plan about 4-5 hours to get into the valley around 5000′ beneath the west face. We got up there in under 4, but had a skin track to follow most of the way. You could camp in this meadow (slight avalanche hazard), or at the 5200′ saddle just west.

The most direct approach would be up a steep snow gully. I would not recommend cutting over to the ridge that trends west from Sloan (which was slow and had obstacles), as we did, unless you are looking for a convenient place to leave skis. This also gives you the option of taking the alternate left hand snow start (orange in the photo and map) that skips the first ice pitch. There is also a speculative right hand start (yellow) to the route, but that ice has a more southerly tilt and looked delaminated. Later, Porter and Tavish climbed an easy mixed pitch directly up the ridge from stashed skis, adding another optional start, especially helpful if stashing skis on the ridge.

On route, I’d recommend carrying 6-8 screws, and optionally, a few light rock pieces and a picket. We only placed one small cam, but the rock is generally decent up there. A picket could be helpful for some anchors, depending on snow conditions.

At the top, you could continue to the summit on steep snow, rappel the route, or head out immediately to the Corckscrew saddle. Once at the Corkscrew saddle, you can ski the high traverse over to the Sloan Glacier and descend off to the north, wrapping back down westward into Bedal Creek from the lower saddle (pink on the map), or take the lower downward trending snow ramp and circle around the south side of Sloan back into Bedal (purple on the map). Note that either option requires crossing that exposed south face of Sloan. Steve turned around here the day before us because of loose wet avalanches around noon. Porter and I were carrying skis up the route so we could cut that traverse quickly and minimize our exposure on the descent. However, we found that rappelling on V threads and natural anchors was surprisingly easy. Thus, when Porter returned with Tavish, they left skis at the ridge and purposefully rappelled the route, making 5-6 60m rappels.

Like most Cascade alpine climbs, conditions are challenging on this climb. I believe the route is in condition most years from sometime in late November/mid December until mid March or so, but I cannot verify any of this so maybe the season is longer or shorter. I’ve seen the face in late fall a few times and although the daggers on the west face are not touching down, our gully route is likely filled in enough to have some solid ice. I’m very curious to check out this route in late fall because you would still be able to drive the road to the trailhead, avalanche conditions would be minimal, and we seem to get frequent spells of cold, clear weather then. The upper snowfields are just a perfect setup to form ice beneath from diurnal freeze/thaw. However, these upper snowfields also pose hazard. They get sun around 11 am and that substantially increases overhead hazard. We encountered a lot of spindrift while climbing, although we never saw any projectile – rock or ice – bigger than a pellet fall during our entire time up there. Still, all these climbs see substantial sun, which is not ideal. For this reason, there are probably just a handful of days each winter where this climb is really safe to attempt. Look for lower freezing levels, consolidated snow, moderate winds, and high clouds to limit solar radiation. The ideal setup would be a warmup followed by a hard freeze and high pressure: terrible skiing conditions are good ice conditions! Regardless, I would recommend starting on this climb at sunrise, moving efficiently, and trying to top out by noon.

Honestly, both Porter and I are really excited to see what happens on Sloan in the next few years. Sloan is a mountain amongst mountains. We believe it is truly a world class venue and if some real climbers got back there in the right conditions, we could see the development of some cutting edge WI6/M6 lines up huge free hanging daggers and madness like that, the likes of which Washington has never seen before. After decades of mystery, we feel it is time to share the secret of Sloan.

To greater heights, to unforgettable sights.

The only way is up.

Damn Kyle that looks like it hurt! Glad your going to be ok.

Get well

Raider Rob

Thanks Rob!

Simply incredible climb and write-up Kyle! As good as it gets, VERY strong work!

Thanks Doug! It was a magical climb! I hope others get after it!

Thanks for the great write up as well.

Thanks Jacob!

Dang, I got a call from a friend on SAR that day asking if I knew anything about an ice route on Sloan and my wife and I have been just watching all of Porters YouTube videos. And really enjoyed the ice climbing blog around Alpental. Keep up the great work.

Thanks Ian!

Thanks for this write up! Wow, what an ordeal! We’ve all been close to that point and as a climbing community it’s important to learn from this.

Thanks David!

Glad you are OK! Nice line done in great style. You’ll be back at it soon enough.

Thanks Dane!

Kyle I dig your blog, heart on your sleeve feelings,glad your okay, as a 60 + year old climber,skier, way to question your actions, you’ll be around a while. Love and death is truth.

Thanks man! I hope to be climbing and skiing still at your age!

Thanks for the great write up and wish you a swift recovery… I’m just curious as to your claim to have made the first winter ascent of the west face. It seems as per your route photos and report that you guys didn’t top out the face. It looks like a valiant attempt but remember just be a little weary of naming an unfinished alpine route and claiming an FA… cheers

Thanks Ethan! Well, I was simply one move from finishing the technical climbing, at which point we would have joined the Corkscrew route. Additionally, I could have taken the earlier snow ramp left and ended the technical climbing. So I guess you could say I was one move short of finishing the route if you want to nit-pick. What if we decided to just end the route where I fell? Plenty of routes end arbitrarily… although I do understand that alpine routes generally want to “top out” on something. As for your comment that we did not top out on the west face, it depends on what you claim the “west face” is. We considered it to be the steep 1000′ lower cliff bands, as it was just moderate snowfields from there to the summit. I believe going to the summit has nothing to do with completing the first ascent of an alpine route. Does Liberty Ridge top out on Rainier? I knew someone would get technical on us… Cheers!

Fuck yeah dude. Way to go for it. This was an awesome write up on such an aesthetic and intimidating looking line from the view of a plane. Sorry about your face, you look like a creature from the Walking Dead… crazy & unfortunate flip to end an almost perfect day. Glad you’re okay, hope the surgery goes well, with only a minor scar to show off your badassery.

Thanks Anth! You’re such an inspiration to me crushing it globally. Hope I can heal fast enough to be ready for you this spring…

That’s a great documentary. It’s informative, has a message and everyone loves pictures. Glad you are healing. Hope to ski with you someday.

Thanks Jim! You know, you are technically the first backcountry skier I ever traveled with back on Mt. McCausland many years ago.

The insane flows on the west face

in the presence of massive ice flows

the gargantuan west face

the biblical west face of Sloan

the wicked ice pillars hanging from the face

It was like the Winter Dance of Washington. Nothing we’ve ever seen could compare. WOW! HYPERBOLE OVERDRIVE

The gully looked absolutely fat and rambly – ideal. yes looked WI3+ MAX anywhere

Porter approaches the vertical curtain. vertical? vertical ice is WI5 minimum

It reminded us of the NW Couloir of Eldorado, but more technical and sustained. really? more technical?? How?

For us, Sloan was never about ego; really? if i didn’t see photos of the the snow gully I’d think you were on the Eiger on a new WI6 climb.

Dude nothing personal and I am glad your okay and wish you well but maybe skiing/hiking is more for you until you get more experience. your writing makes me nauseous and Maybe if you(or anyone!)

would finish the gully then I might be able to stomach this shit. but this makes all Alpinists rather lame. Read about Andrew Deklerk and Julie Bruggers 12 day climb(5 without food) of Hunter’s North buttress or Johnny Watermans shit in Alaska. Also those “new” ice climbs i am sure have been done throughout the last 100 years of climbing in the area, they are practice climbs for real alpine faces.

And since you didn’t post my original comment(guess because it wasn’t praising you and you radness) I expect the same with this one.

I did approve your other “comments” (more like grumpy rambles), so I’m not sure why you didn’t get emailed about that. I agree the gully was WI3+ max. I never said anything else, so not sure why you are so upset… In comparison to Eldo, this route has simply much more ice climbing and less snow climbing – thus more sustained. I also thought the cruxes were steeper than Eldo, but I climbed Eldo in very fat (ie “easy) conditions. The curtain was vertical – congrats, Porter, that means you led a WI5 pitch according to the great Mike Preiss! With skis on your back nonetheless! This also means that the NE Buttress of Chair, with its one little vertical step, is WI5 by the Preiss grading system!

And Porter and Tavish did finish that gully two weeks later… please check your facts.

I agree that I’m “lame” and nothing of a climber compared to those great alpinists that you list. I never will be. I am a normal person who works a day job, has a family, and other hobbies in life. For me, this was a huge experience and achievement. For others, walking up the DC Route on Rainier is, and that’s okay. We all have our unique challenges and goals in life, and I don’t see the value in saying that someone’s dream is better/bigger than another’s dreams.

I guess maybe my writing seems like hyperbole. But you know what also is hyperbole? Claiming Infinite Bliss is “95% the same” route as the Preiss Route. I’m sorry that my writing makes you sick, but it is interestingly your choice to read and follow my blog. It makes me sick to see a once contributing member of the Cascade climbing community regress to become a grumpy, elitist, aggressive arm chair mountaineer. I sure hope I don’t end up like you when I’m an old man.

1st of all I am not “upset” about anything and I said it was nothing personal I was just pointing out your (ego-less?) over hype of a route that has not even been completed (ie summit) or as you said “one move away from completion. maybe if that ice dagger had been touching down would have been different 🙂 Also I’m not following you, it’s the only way anyone can comment on your blog. Enjoy your alpine success and be safe.