Table of Contents

The Kingdom of the Hoh

Each summer, I try to do a big high route in early August, taking advantage of the summer days and hopefully less abundant mosquitoes. In 2019, Daniel and I visited the Brooks Range. Last year, Sam, Logan, and I did the Wind River High Route and Beartooth Plateau High Route. This summer, my goal was to finally experience the local classic: a Pickets Traverse. Sam, Rio, and I had the first week of August marked for an epic week long Chilliwack to Pickets High Route.

July delivered with one of the most perfect months of weather I have ever seen: moderate temperatures, no smoke, and absolutely no rain. But come our big trip, on the climatologically driest weekend of the year, we found an improbable forecast of rain and smoke. There was another front coming at the end of the week and we cut our plans down to a shorter Pickets trip. As the forecast continued to deteriorate, we scrapped the entire plan and threw together a Bailey Range trip plan. In the scramble, we managed to convince our skier/biker friend Nick, who was in between jobs, to come out of hiking retirement and come along. Less than 24 hours after ditching the Pickets plan, we were getting on the ferry, headed to the Peninsula.

The Bailey Range Traverse is the classic Olympic high route that traverses from High Divide to Bear Pass and traditionally exits out the Elwha Snowfinger. We knew vaguely about a longer route that continued onto Mt. Olympus and carried over for a loop. I had not seen many photos or read much about the route, but my friend Colie had just completed the full route over a week, so I called her up for some beta. Caltopo shows a trail the entire way; how hard could it be? Our biggest confusion was how to get permits, since you have to actually call the ranger to get backcountry permits for Olympic National Park. Then there was the scramble to get bear cans for everyone, since they are unfortunately required. But we made the pivot and went with it.

Day 1: Sol Duc to Eleven Bull Basin

The shortest way to do this route is most definitely beginning at Sol Duc and ending at the Hoh, but we planned on doing a loop from Sol Duc to remove the need for a car shuttle. It was humid and drizzling steadily as we loaded our heavy packs and began hiking up towards Heart Lake. But the rain mostly stopped by the time we reached treeline and the overcast skies kept us from baking, so we did not mind. However rainy it was here, it was much worse in the North Cascades, or at least so we told ourselves.

The Bailey Range trail branches off at High Divide and descends into the woods towards Cat Peak. There is no water in this section, so be sure to fill up at Heart Lake. The first clear view of the Bailey Range Traverse, with the Hoh River arcing around to the Olympus Massif, has a close resemblance to the view of the Dakobed Range and Suiattle River Valley from the Image Lake / Miner’s Ridge area.

The only thing I really knew about the route was the “Catwalk”, a section of narrower ridgeline between Cat Peak and Mt. Carrie. There are a few scrambling moves, but really, it is actually one of the easier obstacles on the entire route. I think that many “technical backpackers” do just the Northern Baileys, and for a backpacker, I could see how this section might feel exposed, especially with a heavy pack.

After the Catwalk, the trail continues to traverse the remarkably steep hillside, sometimes descending and ascending steeply in order to find the weaknesses to cross the steep, dirty gullies. As we tiptoed across the loose gullies, we gazed down at a jumble of rocks and choss three thousand feet below us. Slip here and you might not stop until the valley floor. It made us extremely appreciative of the narrow footpath that is established, and impressed with the first party that established this route, given all the hidden pathways and improbable terrain it traverses. Does anyone know the history of the first traverse?

Update – Ben Fox-Shapiro shared with me:

“There are documented Baileys trips going back to the 1920s from Herb Crisler and his crew. I don’t know how much of the northern Baileys they explored, I’ve read some of Crisler’s writing and I only remember him specifically mentioning going in via the Dodger Point-Ludden route (makes sense since he lived at Humes Ranch in the Elwha) and the snowfinger. He had a hollowed out tree where he cached food near Cream Lake, not too hard to find. The CCC drew up plans to build a trail connecting High Divide/Cat Basin with Dodger Point through the North Baileys across the gullies in the late 1930s, but WW2 started before they got any real work done.“

The sky was overcast and air still. No whistle pigs, no chirping birds, no rustling leaves. Just a soaring green hillside, deep Olympic valley, and massive glacial massif across the valley. Purely Olympic.

As we rounded the corner into Eleven Bull Basin beneath Carrie and Ruth, we found streams gushing from the hillsides. Olympic springs have such a distinct flavor – a mossy runnel of scree and green: “screenery”.

We made camp in Eleven Bull Basin, a beautiful spot amongst streams, flowers, and roaming bears.

I love the aesthetics of trips like this, where you can see, from the start, your entire route. It is both scary and enthralling. But as the soft light settled over Olympus, it mostly felt relaxing. After some fast paced, long days in the mountains on Stuart and the Alpine Lakes Crest Traverse, it felt great to lay down in a meadow and know that this was the present and future, at least for a few days.

Day 2: Eleven Bull Basin to Mt. Childs

We began our second day with more sidehilling on a narrow path, moving up and down to get around cliffs and choss. Without this trail, the Bailey Range would be truly tiresome.

We all were tired of the sidehilling, so we decided to go for the alternative Stephen Lake route. As we only had a few hours to prep for this route, we knew nothing more than that some people passed by Stephen Lake. So we climbed up through meadows towards a low pass that would lead us to Stephen Lake.

At the pass, we got a view westward of Stephen Lake and a very hazy Central Olympics. Smoke was moving in from fires in Oregon and California, but it was supposed to get better later in the trip.

Stephen Lake had that glacial torquoise hue, like so many Olympic lakes. A beautiful river delta fed the lake, melting away from some small pocket glaciers tucked beneath the steep spires of Ruth Peak. It was a dramatic and impressive setting. On a map, the peaks of the Baileys look rather unimpressive, but the scale is deceivingly massive in person.

We ascended to about 6000 ft on the north side of Stephen and traversed relatively easy post glacial terrain. This section, with so many little moraines, snowfields, and micro features, reminded me much of Mt. Watson on the Watson Blum High Route.

On the other side of Stephen, we crossed a col and found a well defined trail that eventually petered out into endless sidehilling above lower Ferry Basin. There were many faint trails and it was hard to tell which were human trails and which were game trails. Large herds of elk inhabit this area, as evidenced by some of the giant hoof prints we found.

Eventually, we ended up in upper Ferry Basin, which was, dare I say, an Olympic Ferrytale. There are a handful of beautiful glacial lakes and streams, perfect for an afternoon dip in the heat.

The col between Ferry and Pulitzer is where the Northern Baileys route exits out towards Dodger Point and the Southern Baileys continues. It is also, in my opinion, where the high route levels up. The high travel becomes more pure and the views even wider.

We passed the Lone Tree at Lone Tree Pass, and ascended a snowfield to a high vantage. The air was beginning to clear.

Enjoying the widespread views and easy travel over post glacial terrain, we continued onwards until the basin just north of Mount Childs, where we found a marvelous camp atop a small moraine, perched above a maze of moraines and meadows where the subalpine is slowly reclaiming the land the glaciers are giving up. This was yet another spot that looked so underwhelming on a map but felt surprisingly big.

Either by the timing of the seasons or camp selection, each camp was relatively bug free, and so we were able to lounge in the evenings, taking photos and chatting. July is best for moving quickly (too quickly for the mosquitoes) during long days in the mountains, but August is perfect for slowing down and appreciating a nice sunset or two.

Day 3: Mt. Childs to Camp Pan

We slept in the next morning and then crosses the small Childs Glacier and continued on the Southern Baileys. The Southern Baileys are definitely easier and more open than the Northern Baileys.

The section heading to Bear Pass is a beautiful and open ridge line, a complete joy to travel. The smoke was clearing out and made for some lovely layers across the Olympics.

For much of the Southern Baileys, you walk along ridges with incredible relief to the steep valleys to the west that feed into the Elwha.

The descent into Queets Basin went easily enough. This is where the traditional Southern Baileys exits to the (non-existent) Elwha Snow Finger. However, we continued westward towards the Humes Glacier. Queets Basin is a huge post glacial basin with many streams and moraines. Colie had promised bears here, and sure enough, we saw a bear.

Part of what I appreciated about the Bailey Range is the transitions from alpine to subalpine and back. Some traverses, like the Ptarmigan, stay so high the entire time. As a result, you miss the sections where streams join and twist into a braided gravel bar, where gravel bars give way to heather. The Baileys travel through all biomes, as we were about to discover the hard way.

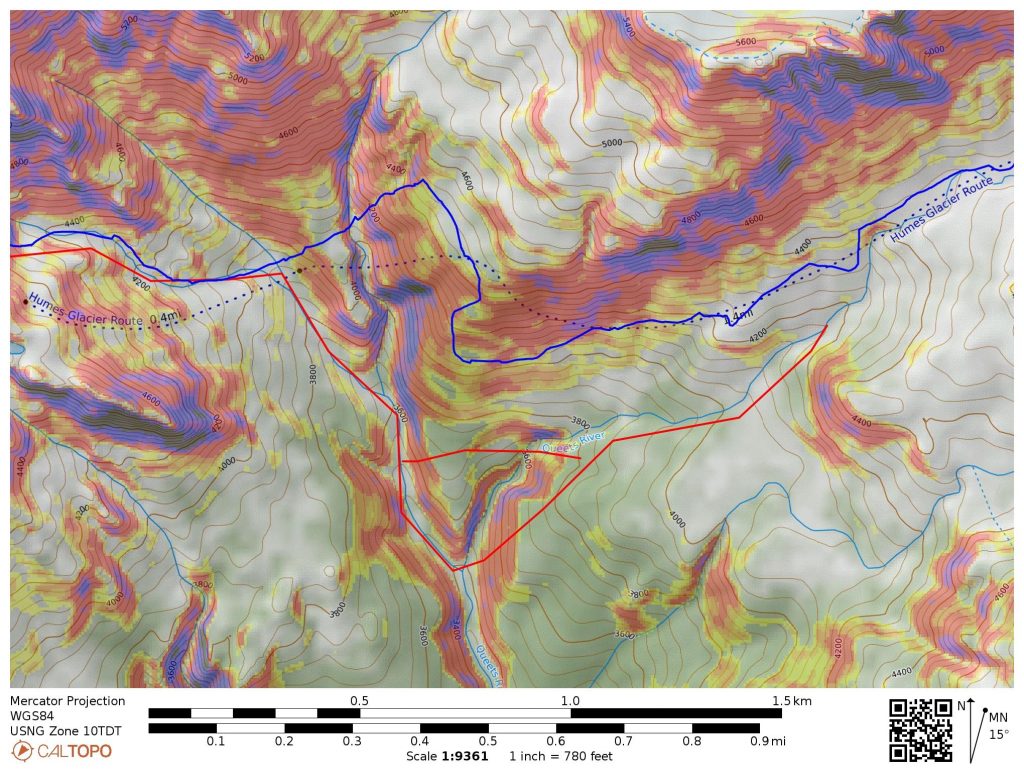

We expected the section from Queets Basin to the Humes Glacier to be the crux of the route. Colie shared some waypoints that traversed really high. It looked annoyingly roundabout. The caltopo line goes more straight through, crossing some very steep ravines. It started out well enough, traversing a well trodden path across a brushy hillside. But it seems that these trails were elk trails, not human trails, and did not lead us exactly where we wanted to be. So we schwacked up the hillside and kept traversing. Somewhere along the way, Nick stumbled upon a Garmin watch. If this is yours, let us know!

Eventually we got to a bench around 4500 ft and could see the terrain better. The higher route looked really long and still challenging, so we decided to try to cross the ravines, like the Caltopo line. A steep descent on veggie belays and gripping flowers for holds in the perilous dirt led us to the base of the first ravine. It was a dry slot canyon, so we followed it downwards to where it joined the second ravine. Here, the ravine was filled with an impassable snow bridge – can’t go around it, can’t go over it (too thin), guess we gotta go through it! I held my breath and darted through the snow to cross the river.

On the other side, we were able to chimney out of a moat and climb up a dirty 4th class gully. Finally the ravines were behind us. A little more schwack brought us finally to an open gravel valley and an easy ascent up to the terminus of the Humes Glacier.

Looking back, I think a lower route would be much better. I am not sure why everyone tries to stay so high, sidehilling through nasty terrain. The elk obviously have well established trails lower down through beautiful brush free meadows. Then a gravely river could be ascended from 3300 ft up to where we climbed up to the Humes. No guarantees, but I highly suspect this would be a more pleasant line. Our route wasn’t really that awful, but it was a rough schwack for about 2 hours.

Another alternative is to actually traverse the north side of Peak 6130, bypassing the Humes Glacier and Queets Basin entirely. This sounds like the fastest way, at least, when there is good snow coverage. Late season supposedly it requires crossing some steeper ice and lots of choss.

The Humes Glacier terminus is rapidly receding, and has left a glacial terminal moraine lake that has formed in just the last decade. There were some small pools of stagnant water that were warm, like Lake Washington in the summer. They were also full of frogs.

Very few times in my life, if ever, have I climbed onto a glacier from the terminus. In the Cascades, that is usually a terrible idea. But these glaciers are so flat that it works. So we put on crampons, roped up, and walked onto the bare glacial ice of the Humes Glacier. Streams ran through the ice and disappeared into the moulins. It was a really cool experience.

Incredibly, we found giant hoof prints on the Humes, likely belonging to elk! The Humes was easy to cross and soon we found ourselves climbing up to Blizzard Pass, which would lead us over to the Hoh Glacier and Camp Pan.

For us, it was an unusual experience to go into a trip with so few expectations or preconceptions. None of us had read many trip reports or seen photos from the route. Each turn was a surprise. All I knew about Camp Pan was that Colie said we should try to camp there. This was a massive understatement!

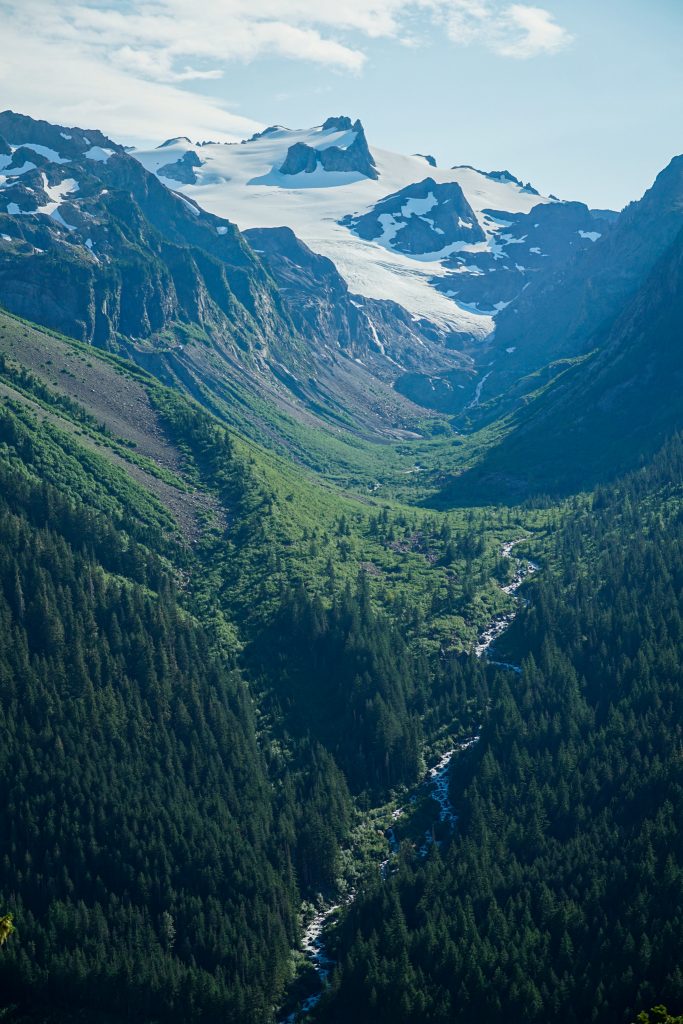

As we crested Blizzard Pass, we entered a new, hidden kingdom of rock, scree, and ice. The Hoh Glacier descended 3000 ft over 3 miles in a giant river of ice, beneath towering peaks above. It felt like a setting so absurd, so grand, it could not possibly be in Washington. The Alps? Alaska? Pakistan? No, this was Olympus, the secret Kingdom of the Hoh.

Camp Pan could not have been more obvious – a dramatic prow jutting out hundreds of feet into the glacial valley, perched high above the Hoh Glacier. The position looked absolutely dreamy.

Up until this point, the Bailey Range had been really good. The Kingdom of the Hoh elevated the trip into the pantheon of high routes, not just in Washington, but the entire lower 48. Can you get this position anywhere else in the lower 48?

Camp Pan has a bunch of flat, sandy campsites. Walking around in bare feet, void of bugs, running water nearby, with otherworldly views, we all agreed that this could be an all time top-5 campsite.

At our previous camps, we were soaring high above the valleys, but on this evening, we were perched like guards to a kingdom of ice, closed off on nearly all sides from the world of green, the world we were familiar with. In some ways, we could not have felt further from Washington. In other ways, you could say nothing else was so Washington.

Day 4: Camp Pan to Hoh River

I woke up to go pee in the middle of the night and was amazed at the darkness of the sky – no moon, minimal light pollution. So I grabbed my camera, made a tripod with some rocks and did some rare night photography.

We woke up at sunrise, since we knew this would be a long day with an Olympus summit. The sun rose nearly straight up the Hoh Valley.

We followed some snow ramps and rock ledges down to the Hoh Glacier. There is really only one reasonable way down to the glacier, so it felt pretty obvious.

The Hoh Glacier was pretty simple to cross and then we did a long snow traverse to reach the pass.

From there, we dropped down onto the Blue Glacier, spotting some other climbers, the first people we had seen in three days.

We cached our overnight gear where we left the Blue Glacier and started climbing up snow and slabs towards Snow Dome. This part of the route was familiar to me, since Daniel and I had done Olympus two summers ago.

When Daniel and I climbed Olympus, we climbed directly over the bergschrund to the summit block. This time the bergschrund was obviously out, so we took the longer Crystal Pass Route. All I can say about this route is it is one of the worst mountaineering routes I have ever done – painfully circuitous, up and down, with plenty of nasty scree. Would not recommend.

When we finally reached the summit block, we looked directly up the steep north face. This is where Daniel and I had climbed up previously, but we had some nuts and a dynamic rope. This time, we only had 6mm static RAD lines, so someone had to solo the summit pyramid. Nick climbed up first, and his grunting suggested moves harder than the supposed “5.3” grade. Apparently, the 5.3 route is around to the right, but none of us knew this. Nick fixed a line and the rest of us climbed up with a micro traxion. What we did climb was very solid and featured one 5.7ish move that would protect well with medium nuts.

At the summit, Rio pulled out some homemade coconut treats, which he had been hauling around for four days for this moment! We were ecstatic. In addition to being an all around solid guy, Rio is a great baker! Hear that, ladies? He’s single!

From Olympus, the Bailey Range looks rather small and lame, but it was still pretty cool to see the entire route.

We did one rap (a 30m rope would be sufficient, but we tied our two ropes together) down the actual 5.3 route and then reversed the painful Crystal Pass route.

When we arrived back at our cached gear, Nick discovered that a stream had unfortunately formed where his gear was placed! His sleeping bag, camera, and – worst of all – cribbage board were all soaked! Then Sam discovered he had left his crampons back up near Snow Dome and had to go back and get them. Unexpected cumulonimbus clouds were building to the west. Rio had commented that things were going too well…

Nick dried out his gear while Sam went back for his crampons. Thankfully a group of guys had picked them up, so Sam did not have to go all the way back up. Then we raced across the lower Blue Glacier to the other side. With the bare, exposed glacial ice, it felt like boulder hopping, but with crampons on ice. It was kind of fun.

Then it was just one last steep climb to the lateral moraine before finally returning to nice trail for the first time in a few days.

We were all pretty tired, but we managed to plod down the trail past Glacier Meadows and down into the Hoh Rainforest. Nick and Sam used to lead trips, so they are well versed in corny riddles and games to pass time. The paramount debate was: “is a hotdog a sandwhich?” We asked some others on the trail, who responded “meat slapped between bread, so yes”. Perhaps the greatest analysis of this question can be found in The Cube Rule.

We reached the epic bridge above the Hoh River and lounged on the bridge, tired from a long day. This is one of my favorite spots in the mountains, a deep mossy slot canyon with blue silty water roaring hundreds of feet below. From the high glaciers to the temperate rainforest, the diversity of terrain on this trip was wonderful.

We found a flat beachside camp along the Hoh and crashed for the night after a long day. We fell asleep to the roar of the river.

Day 5: Hoh River to Sol Duc

Most groups seem to do a car shuttle between the Hoh and Sol Duc Trailheads. But we wanted to do a simpler loop, so we had to end our trip with a 4300 ft climb back up to High Divide. The climb up to Hoh Lake surprisingly goes through an old burn zone and has a fair bit of blowdowns. Our packs were rather heavy for the last day, but that owes to the fact we had glacial gear, crampons and ice ax, and bear cans. We were all basically out of food.

It was kind of cool to return to the alpine and get one last view at the entire Bailey Range Traverse. The route idea is so simple and obvious – and sometimes that is what makes a traverse classic.

The descent from Deer Lake was annoyingly rocky, but it went quickly enough. At Sol Duc Falls, it was a bit of a shock to run into crowds of tourists. Our odor might have been a shock to them. A swim in the crystal clear waters of Lake Crescent hopefully fixed some of that before the journey back to the other side.

The Bailey Range Traverse was a truly stunning high route with the most variety of terrain – meadows, post glacial lakes, huge valley glaciers, and old growth rainforest – of any route I have experienced. It does not seem to get the recognition of classic routes in the Cascades like the Ptarmigan or Pickets, but it certainly deserves equal status. While we were disappointed to “settle” for the Baileys, it ultimately did not feel like a backup trip at all, and this trip will certainly be one I will remember for a long time. This traverse should be a bucket list high route for any Washington High Router.

From the temperate rainforest to the giant glaciers, the Baileys are the wild heart of the Olympic Mountains – remote, rugged, and spectacularly beautiful. I am grateful for five memorable days in the Baileys with Nick, Sam, and Rio. Maybe we’ll get the Pickets next year!

Notes:

- Curious about what gear we used? See this post about my favorite high route gear.

- For our route, including the Olympus summit, we measured 61 miles and 26k ft gain. It felt pretty reasonable over 5 days. Most of our days were about 8-9 hours with long swimming breaks and lots of photos. Our fourth day was over 12 hours long with the Olympus summit.

- Comparisons are often the best way of measuring the difficulty of a high route. The obvious comparison is the Ptarmigan. Overall, the Baileys felt consistently more difficult. Not technically more difficult, as it rarely exceeds class 2, but just slower travel, more routefinding, less defined of a trail, more sidehilling, etc. The Ptarmigan is much more cruiser.

- We rarely consulted maps or phones for navigation. It is generally pretty obvious where to go. The exception is the section before the Humes glacier, which I already discussed.

- While this route has a reputation for bushwhacking, there was not really any bushwhacking other than the section before the Humes. There was lots of “bushbashing”, but that is different – not as bad. Sections of the trail were “brushy”.

- For footwear, we wore running shoes and brought strap on aluminum crampons. This worked very well. Hiking so much in heavy mountaineering boots would be painful. The snow was mostly low angle so burly trail runners like the Ultra Raptors worked well. Definitely bring crampons, not microspikes, for the exposed glacial ice.

- For our glacial kits, we used standard skimo kits: 30m 6mm RAD line, tibloc, microtrax, pulley, and some slings. I don’t think an ice screw is needed because there is really no way to fall in a crevasse in the bare ice sections, even if you tried. A picket is a personal decision, and I almost never bring one for crevasse rescue, especially in a large group where ice axes are plentiful.

- Doing this route over 5 days really gave me a new appreciation for our friend Jeremy, who soloed the route in a single push! Mind blowing! Read his trip report here.

- Permits are now obtained over the phone for backcountry off trail camping on Olympic National Park. Thus, a bear can is required, unfortunately.

- Some people do just the Northern Baileys, which seems like it would be 75% trail walking below tree line for a relatively short alpine section. The Southern and Northern Baileys would be a worthwhile trip while not requiring glacial travel. But the grand traverse with Olympus definitely felt like the most bang for your buck. In fact, if you consider climbing Olympus typically takes 3 days, this trip was only an additional 2 days and covered so much more terrain.

- There are generally abundant beautiful camps. The main section without good camps is between High Divide and Eleven Bull Basin, where there is no running water.

- If done later in the season, one might run into some bare ice descending from Blizzard Pass to Camp Pan, although I am not sure how the snow melts out.

- It seems the ideal time, in terms of snow coverage, is mid July through mid August. I would not go earlier because sidehilling steep snow in the North Baileys would suck. Late season might work, but there will just be more bare ice.

Cool writeup, I was supposed to be doing something similar last week but I broke my foot so its bittersweet to read your report. With regards to your question about the first traverse, there are documented Baileys trips going back to the 1920s from Herb Crisler and his crew. I don’t know how much of the northern Baileys they explored, I’ve read some of Crisler’s writing and I only remember him specifically mentioning going in via the Dodger Point-Ludden route (makes sense since he lived at Humes Ranch in the Elwha) and the snowfinger. He had a hollowed out tree where he cached food near Cream Lake, not too hard to find. The CCC drew up plans to build a trail connecting High Divide/Cat Basin with Dodger Point through the North Baileys across the gullies in the late 1930s, but WW2 started before they got any real work done.

Thank you Ben for the history, I updated my story with your information!

Sorry to hear about the broken foot. Hopefully you can get out to the Baileys next year!

There are books about the Crisler. They are very interesting! An Olympic Mountain Enchantment is the easiest to find. https://www.amazon.com/Olympic-Mountain-Enchantment-Interlude-Photographer/dp/B00948MV4W

I’ve only ever found one copy of “Olympic Mountain Wilds” which I added to my library. It’s about Herb as well, by the same author as the book above. It may come up once a year if you keep an eye out for it.

There are AMAZING stories about Crisler. Think homing pigeons, injured and taking weeks to get out of the mountain, filming for disney in the Olympics, going for a month with no food or gun on a boast, so forth. I’d write more about the subject, but it’d be far too long. Check out the sources above if you are interested.

Sounds wild Jason! Herb must have been a beast. Thank you for the references, I bet you read a lot about him during your research.

Most certainly. The focus at the moment is Mt. Rainier, though. I’ll probably bite off Mt. Saint Helens next, then the Olympic Mountains. All my preliminary research is done, but the more focused research takes much longer. The section I’m writing on Mt. Rainier will be around 60 pages of writing, but each paragraph is sometimes 3-5 books of research to write with any bearing on the subject.

Anyhow, I really want to get out here in summer. Doing that traverse again without skis would be great.

Wonderful writeup! Justin McGregor and I did a similar route in 2019 that was spectacular. It was a 3.5 day push so couldn’t tag Olympus in the interest of getting home to our doting wives and children…

One interesting side note is that we found some plane wreckage around the base of the Humes and I was actually able to get in touch with a guy who had found the wreck and maybe one of the pilots in the 50’s.

We went in the Hoh and out Dodger Point. DP is a great way to exit with less sidehilling, but requires a shuttle.

Interesting, was the Humes wreckage coming out of the glacier because the glacier was receding? But then how had the wreck been found earlier?

This trip looks incredible and one that I can definitely work my way up to. Gotta keep practicing glacier travel, routefinding and rock scrambling. One day I’ll do this one. As usual great report Kyle!

Thank you Bradley!

Great report Kyle. Love the idea of adding Olympus to a Bailey trip. Would you be willing to share which crampons you’ve had success with pairing with trail runners?

I think most strap on crampons are fine, although the metal linking bar definitely adds some stiffness (and weight). The Petzl Leopards are liked by some, but others feel they are not as good because they don’t have the metal linking bar. I think it is a tradeoff. The Kahtoola crampons are specifically designed for trail runners and seem really good too.

Hi Kyle, thank you for your detailed report. Pam Baker and I did mostly the same loop on August 15-20, 2022 except: 1) we went up and over Mt Carrie, up the Fairchild glacier to Stephen lake basin, and 2) we did not include a summit of Olympus.

Your notes here on crossing the Queets basin over to the Humes glacier were perfect:

“Looking back, I think a lower route would be much better. I am not sure why everyone tries to stay so high, sidehilling through nasty terrain. The elk obviously have well established trails lower down through beautiful brush free meadows. Then a gravely river could be ascended from 3300 ft up to where we climbed up to the Humes. No guarantees, but I highly suspect this would be a more pleasant line.”

Your text here is exactly perfect but your sketched lines on your figure go through too steep terrain. We followed the low angle slope on mostly well established game trail right to 3300 ft where at the Queets river junction. Then up the river. Was very easy, and yes, pleasant. Following the guidebook/traditional route (?) which traverses steep thick gullied terrain here looks like a route choice that would be unpleasant and take a lot of time. I’m puzzled why that route is selected.

My looking back comment would be just to spend and extra night or two out, to allow for more R&R and side exploring. Thanks again!

Wow that is so helpful, thank you for letting me know that it worked out! If, or when, I go back, I will definitely go that way and that removes the most unpleasant part of the Bailey Range. Glad your trip went well!

Can we play my favorite game for a second? It’s called “How bad of an idea is it?”

My partner, another friend, and I, are considering the Bailey Traverse this Labor Day. Just came off the Ptarmigan last week and are hoping to squeeze in another traverse this season.

Permits acquired and stoke is high, but how bad of an idea is it to give this a go during the first week of September? We’d likely be taking on the same route you did. A secondary option would be to simply do Olympus and back and then return next year for the Bailey. Any strong opinions either way? I’ve heard the tongues of the glaciers in the Olympics can be a bit icy at this point in the year. I appreciate any feedback. Thank you.

I think the Baileys will be fine over Labor Day. The glaciers are very flat so although they will be icy, they should be easy to deal with.

Regarding the routes through the Queets basin, in 2021 three of us also spent quite a bit of time investigating different routes. We found by staying low one could get 500 or 600 feet from where the creek coming off the Humes meets the Queets without too much trouble (i.e. merely bushbashing and pretty much no gullies or ravines to navigate). At that point , we found a steep wooded slope beginning at 47 47 04 16 N 123 37 14 47 W which could be easily descended to a flat spot at the bottom (at 47 47 04 64 N 123 37 16 12 W). From there, there was maybe a 10 – 15 ft drop to a dirt slope down to the river. We ended up not doing this, but it does seem manageable by setting up a belay off a tree in the flat spot down to the dirt slope (alternatively, there was a spot where you walk out a little further and possibly hop down onto the dirt slope). It would be helpful if Zeno Martin could comment on whether this is what he found or not and how he managed this.

I guess considering we had glacial gear, we could have just rappelled in that situation. Definitely seems better than going through the heinous sidehill terrain we did.

We stayed at the lake just west of Dodwell-Rixon Pass. From there on our way to the Humes glacier we followed the drainage from this lake down, staying north of it, all the way to 3310 ft (47.77896, -123.61890). On our way to the low spot I’ve identified, we did eye the terrain more north and west of our route, and more direct, but it was too steep. Instead of dealing with too steep terrain, we followed the relatively lowest angle slope down to the low spot I’ve identified here. Well established game trails also follow this easy route making it easy. From the low spot we hiked up the creek drainage to the Humes.

While hiking up the Queets river and up into the creek drainage toward the Humes, and looking right and up, I didn’t see any obvious easy (non rappel) access ways coming down to it.

Thanks Zeno! That’s exactly what I see on the caltopo slope angle shading. Looks like further north you will encounter steep gullies.

Zeno, thank you very much for these details – this is a little different than what I thought – essentially after leaving the lake near D-R, you never cross the Queets , but instead stay on the south side of it until you descend down to it. If I have got the coordinates right, the point at which you are finally on the Queets riverbed at 3300 ft, you are about 1800 ft after the point at which the creek from the Humes joins the Queets. Correct?

Kyle,

I’m grateful for your detailed trip report. I’d been interested in the Bailey Range for a few years before deciding I was ready to do it this past spring. Your loop route across the glaciers of Olympus and back to the starting point was inspirational!

I solo hiked a similar route to yours over 7 days starting July 27, 2022. It was my first time doing anything of this level of difficulty. I did not climb Olympus, and I attempted to go over Mt Carrie as your friend Jeremy had done, but turned around due to problems finding a suitable route up the ridge. In retrospect, after gaining more confidence, I think I could have climbed the snow field on the face of Mt Carrie and continued with that route.

I’ll add my story to the discussion of getting from the Queets basin to the Hume Glacier. I planned a route per your suggestion keeping a lower line on the north side of the Queets river. It turned out to be a very nice way to get to that ridge above the stream coming down from the Hume. At that point, I made a series of attempts at different places to descend the steep slope, but turned around when I decided they were not safe. I gradually worked my way down towards the point where that stream joins the Queets. I eventually found a route down via some less steep sections and the trees growing sideways out of the hill.

I then found it quite challenging ascending that stream valley toward the Hume. Perhaps the water flow was more when I was there. I decided to go up along the left bank of the stream a bit away from the water flow. It was a horrible long bushwhack pushing through dense vegetation. I may have been better off scrambling over the boulders of the streambed and trying to stay out of the water.

I also had some difficulty finding a safe route up the rock faces below the Hume basin. I eventually topped out well above the snout of the Hume (what an incredible sight!) and worked my way down to it.

I was anxious more on this trip than on previous solo backpacks (mostly on well-developed trails) due to dealing with the steep conditions (rock and snow), route finding and bush-whacking. I developed a lot more confidence traveling on steep snow slopes and actually found that part to be relatively easy. I think the time of year and the heat helped. It was easy to plunge my ice axe deep into the snow for a reliable self-belay.

Thanks again for sharing so much detail about your trips. I’ll be reading some of your other trip reports as I consider more adventures.

Wow that is an adventurous solo trip Ken! I’ve heard many stories about that section now. Sounds like the high water flow made it much harder for you.

What a great account, an almost dreamlike experience.

Awesome trip and report. Planning to do the same in a few weeks. Would you be willing to share your gpx with me? Thanks

Sent you an email.

Really appreciated this post — and you inspired me to upgrade my camera gear. Planning to do this route in late July / early August. Would you be willing to share your gpx with me as well? Thanks.